Below, I offer eyewitness accounts of two noteworthy theatrical productions designed by the cult icon Edward Gorey before pop celebrity descended on his far from willing brow. The first, a postage-stamp Dracula on the faraway island of Nantucket, presaged the pharaonic blow-up deposited on the stage of Broadways's Martin Beck Theatre several seasons later. The second, a one-off Don Giovanni in Manchester, New Hampshire, sank without a trace. At a guess, the director Peter Sellars, in his wunderkind phase, took a hard look at the show and realized that Gorey's aesthetic preempted his own. For the landmark Mozart-Da Ponte trilogy Sellars went on to stage he drafted better team players.

Gorey's prose, verse, and graphics have had their niche in my palace of memory since my college years in the late 1960s. Yet the reports that appear below constitute the sum total of what I ever had to say about him in print. Truth to tell, I would be content to let them R.I.P. in my clip file until the crack of doom were it not for the late boom in Gorey studies, which include the odd reference to the shows in question but nothing by way of first-hand impressions.

From the 1970s into the early 80s in Manhattan, Gorey's histrionic persona passed before my eyes on countless occasions, especially during intermission at performances of George Balanchine's New York City Ballet. Though I was on friendly or at least on speaking terms with several people in his circle there, one degree of separation always remained. I don't recall ever hearing the distinctive sounds of his voice, which Mark Dery evokes with no little insistence in Born to Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey.

From the 1970s into the early 80s in Manhattan, Gorey's histrionic persona passed before my eyes on countless occasions, especially during intermission at performances of George Balanchine's New York City Ballet. Though I was on friendly or at least on speaking terms with several people in his circle there, one degree of separation always remained. I don't recall ever hearing the distinctive sounds of his voice, which Mark Dery evokes with no little insistence in Born to Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey.

But then, Mr. Dery insists on every point he makes, by exaggeration, by repetition, or both. High on the endless list of his acknowledgments, he recognizes Michael Szczerban, executive editor at Little Brown, "who did battle with the Leviathan [i.e. Mr. Dery's raw manuscript], slashing it down to readable size with just the right mixture of sensitivity and steely resolve."

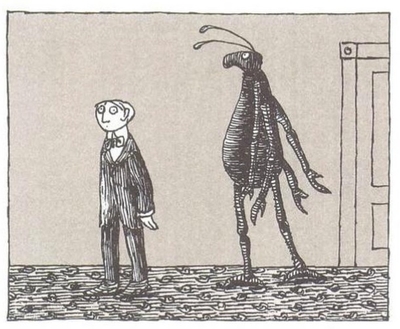

Gorey: The Bahhum Bug (with Edmund Gravel, left). |

Seven years aborning, Mr. Dery's Leviathan whupped Mr. Szczberban's butt fair and square. The beastly baby weighs in at 513 pages, an easy 314 over fighting trim. Gorey's life was not rich in incident. Narrative interest lies chiefly in the alien worlds he explored—beyond Gulliver, beyond Captains Kirk or Cook—in books, movies, ballet, and art. Inspired criticism of Gorey's creations might have justified a few dozen extra pages, but there's the rub. While Mr. Dery—a self-styled "cultural critic" who prides himself on the coinage Afrofuturism—indeed dabbles in critique from time to time, the inspiration simply isn't there.

Notionally his subject's first biographer, Mr. Dery is a researcher to warm the cockles of the cold heart of George Eliot's Edward Casaubon, constitutionally unable to leave the least pebble unturned. At that, his reliance on Alexander Theroux's memoir The Strange Case of Edward Gorey (2011), duly cited dozens of times in Mr. Dery's pages, verges on cut-and-paste if not outright plagiarism, citations by the dozen notwithstanding. Mr. Dery proceeds chronologically, Mr. Theroux by the random walk of free-association, but no matter: they cover the same map.

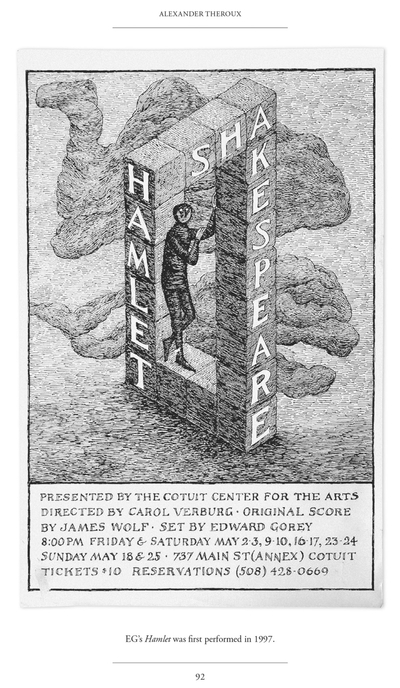

Dare I say it? Mr. Theroux could have used a blue pencil, too. Compiling lists is a tic with him, as is the spouting of verse no one you're likely ever encounter has ever read, by luminaries no one you're likely ever to encounter has ever heard of, sequined with quotes and spicy with scandal. Like Mr. Dery, Mr. Theroux repeats himself (fur coats, Keds, rings and pendants, anyone?). But let's cut the man some slack. His canvas measures a tight 96 pages, text leavened by rare snaps and ephemera—this Penrose-quadrangle flyer for Hamlet, for example, wittily emblazoned with a cloud very like a camel and another very like a whale.

Dare I say it? Mr. Theroux could have used a blue pencil, too. Compiling lists is a tic with him, as is the spouting of verse no one you're likely ever encounter has ever read, by luminaries no one you're likely ever to encounter has ever heard of, sequined with quotes and spicy with scandal. Like Mr. Dery, Mr. Theroux repeats himself (fur coats, Keds, rings and pendants, anyone?). But let's cut the man some slack. His canvas measures a tight 96 pages, text leavened by rare snaps and ephemera—this Penrose-quadrangle flyer for Hamlet, for example, wittily emblazoned with a cloud very like a camel and another very like a whale.

Mr. Theroux's knowledge of his subject, his friendship with him, his clairvoyance, and even his exasperation catch truths of one sort or another at every turn. Yet Mr. Dery rakes him over the coals, repeatedly, for an erroneous weather report. "[Gorey's] body was cremated," begins the final sentence of The Strange Case, "and his ashes were strewn over the waters at Barnstable Harbor on a day overcast and gray and hammering with rain."

Au contraire, Mr. Dery announces, it was "'a lovely, sunny warm day,' as [Gorey's cousin] Skee [Morton] recalls it," "a bit of meterological humbug" Mr. Dery applauds even in the same breath as "appropriately Goreyesque."

Appropriate, indeed. As Mr. Theroux confesses, he had not the heart to attend. Mind you, Mr. Dery was not there, either, nor anywhere else in the artist's living ambit. Se non è vero, è ben trovato. Let's hear it for pathetic fallacy.

*

Dracula

Adapted by John Balderston and Hamilton Deane

At the Cyrus Pierce Theatre, Nantucket

The Real Paper (Boston), July 25, 1973

The newly formed Nantucket Stage Company - whose very location consigns it at least to literal insularity - might sound like a promising, candidate for instant oblivion, but its inaugural production, a brilliant revival of the classic of vampire literature, commands far more than casual attention. NSC's inspired "Dracula" introduces Edward Gorey, author and illustrator of concise, arch, macabre literary parables, in the role ·of stage designer. Since Mr.Gorey neither supervised the actual execution of sets and wardrobe, nor attended opening night, one suspects that he has small intention of embarking on a great theatrical career. That makes his debut doubly precious, and anyone familiar with his shadowy, somber graphics will appreciate how perfectly suited to his talents this tale of fear and horror is.

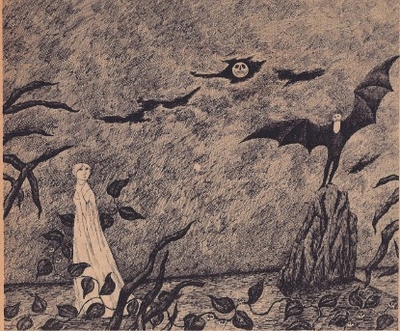

Mr. Gorey is in the very heart of his own territory here, so one can hardly quibble if he has elected to set this Victorian period piece not in a recognizable London suburb but under vaulted Gothic ogives. Atmosphere, not slavish historical accuracy, is clearly his aim, and he has masterfully conjured up an aura of creeping evil where bats and skulls lurk in every corner and even flower petals leer with skeletal grins.

Like his best graphic work, Mr.Gorey's "Dracula" is meticulously stylish, and in severe black and white. Here, though, he allows a rare spot of red - a rose, a jewel, a ribbon - the effect remains, in true Gorey fashion, unyieldingly grey. The translation of a graphic artist's work to any animated medium is intensely risky, and to my mind almost never successful. Think of those pathetic cartoons of "Peanuts." But here, the artist's style has survived dazzlingly intact – so much so that the use of human actors could well have seemed intrusive. But it did not.

It is unlikely that anyone today could actually be frightened by "Dracula." Thus, it would be easy - and cheap and not, presumably, very funny - to play it as sheer camp. Instead the company, under the deft and witty direction of Dennis Rosa, has cleverly translated "Dracula" to the realm of high comedy, perfectly consonant with the Gorey settings, carefully balancing delicious horror and morose mirth. The text is played with intensity and high seriousness, overtly aiming neither for laughs nor feverish terror; what results is a disarmingly hilarious comedy of manners invaded by an exotic ghoul.

This concept is so tight and strong that--implausibly--even the serious miscasting of the title role flaws the evening only negligibly. Lloyd Battista, whose "Transylvanian" accent is distinctly reminiscent of Daniel Massey's Italian accent in his role as the Prince in the BBC's "Golden Bowl," lacks both fatal charm and morbid fascination. One longs for Bela Lugosi.

But the rest of the cast is uniformly superb, especially Ann Sachs as the heroine, Lucy Seward. Her imaginative performance contrives to parody high strung anguish, upper class boredom and erotic abandon without ridicule; she vacillates astonishingly between passionate concern for her fiancé and the overwhelming compulsion to have at his neck.

Great talent and hard work have merged to make this "Dracula" impressive and enjoyable. This is the stuff, in gorgeous, living black and white, that memories are made of.

*

Don Giovanni

Opera News, December 13, 1980

(Manchester, N.H.) Switchblade murder, a bride in black, a nude on a bicycle--these are images from the Manchester Don Giovanni, and the fun had just begun. By the time it was over, the hero had mainlined, fondled his mandolin through a serenade to an electric fan and littered the stage with bills for no more festive a banquet than a Big Mac.

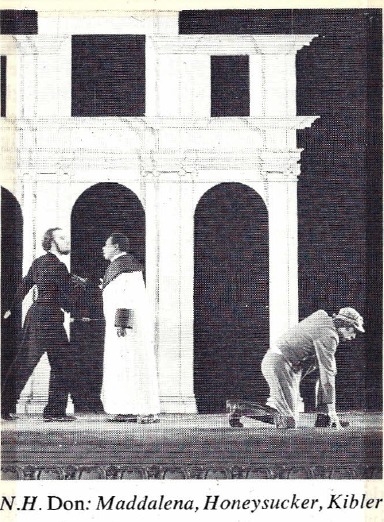

Musically, the production was a labor of love. After weeks of painstaking rehearsal, the New Hampshire Symphony under director James Bolle played with crispness, clarity and passion, scoring many telling points, notably in the shifting moods of the Act II sextet. Among the singers, Susan Larson (Elvira) swept the honors with precise dramatic accents and intense yet lambent vocalism.Keith Kibler's bass is by nature too rotund an instrument for Leporello's buffo patter, but his portrayal came closest to matching her standards. At first deadpan and listless, Nancy Bergman's Zerlina suddenly broke into radiance with a lovely, caressing "Vedrai,carino."The inaudible Masetto, Robert Honeysucker, doubled as an awesomely booming Commendatore. James Maddalena's dominant tone in the title role was a snarl. As for the Donna Anna of Mary Lindsey and theDon Ottavio of Frank Hoffmeister, a chasm yawned between their evident good intentions and the results.

Theatrically,the show was anact of vandalism.No blame falls on designer Edward Gorey, who in his opera debut set the stage in his spidery fashion and peopled it with actors who loosely evoked the Roaring Twenties.How aptly figures like those in Gorey's books, with their hearts of mystery and their robotlike singleness of purpose, might have filled the roles of Mozart's dramma giocoso was made plain again and again in pointed details. But metteur en scène Peter Sellars (a June graduate of Harvard, among whose credits are an Antony and Cleopatra staged in a swimming pool and a one-evening adaptation for puppets and people of Wagner's Ring) kept shattering the frame.In the introduction Giovanni and Anna entered from separate doors and proceeded to sing straight out to the audience, not to each other.

Many of the opera's most eventful moments found Sellars similarly unwilling or unable to invent anything for the singers to do. On the other hand, he swamped more static passages with business, proving his repertory of jokes to be repetitious and thin. An attempt to "choreograph"the asides in the quartet fell flat because of sloppy geometry. In the second act, his crackpot ideas gradually began to converge. Ottavio, sposo e padre, sang "Il mio tesoro" while mounting an empty pedestal and donning the Commendatore's nightgown; Masetto sang the statue's lines from behind its base. In the finale, the tenor and bass filled the same separate visual and vocal functions while Elvira grimly stoked the dry-ice machine to raise the smoke of hell and Anna, an extravagantly plumed Fury, sent the evildoer off with a vampire kiss.

The culmination had undeniable energy and terror, but getting there was about as cheering as watching a madman slash old masters at the Rijksmuseum. Sellars sometimes did show a more benign spirit of experimentation, like Duchamp's: the nude on the bicycle appeared in Leporello's catalogue, a discreetly pornographic fin de siècle slideshow.