The historic Avignon production of Paul Claudel's Le Soulier de Satin in 1987 lasted all night. Marc-André Dalbavie was there, and it changed his life. Now, his new opera lets music do the work of much of Claudel's epic text, bringing the running time down to some seven hours--a lot less than that of the Ring cycle but still longer than Götterdämmerung. |

Nominated six times for the Nobel Prize, Claudel had a long-running day job as a French diplomat, serving in posts from New York to Shanghai, Prague to Rio de Janeiro. He published his magnum (correction: maximum) opus in 1929, with faint hope of ever seeing it performed by actors of flesh and blood. Yet in a handful of productions beginning in the 1940s, Le Soulier de Satin has proved a sensation. The full monty clocks in at 12 hours. Dalbavie has whittled the running time down to seven, which still out-Wagners Wagner.

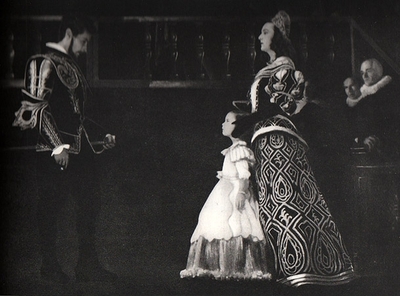

Such a marathon might seem forbidding at the Bastille, the Paris Opéra's no-frills contemporary auditorium. Ah, but the company is mounting the show at its gilt-and-red-velvet temple to glamour, the historic Palais Garnier, which sheds starlight on all who enter, greatest to least. See and be seen! Each has a role to play, as at the Sun King's Versailles. Who could devise a better setting to celebrate or, indeed, to deconstruct Claudel's fantasy without borders?

On Zoom from his home in Périgord, five hours to the southwest and a world away from Paris, the composer reflects on this staggering project.

MATTHEW GUREWITSCH: Despite his play's epic length, Claudel managed to summarize the action in Le Soulier de Satin in just one sentence. Loosely translated: "Two starry lovers from opposite sides of the Milky Way catch a glimpse of each other once a year but can never meet." That makes Tristan und Isolde sound like a walk in the park. It's so earnest!

MARC-ANDRÉ DALBAVIE: Yes, but a lot of the piece is also very funny. Often, while writing the music, the situations made me laugh out loud. Claudel mixes comedy and romance and fairy tale and adventure and tragedy very freely, like Shakespeare. Claudel always said that he was influenced by the theatrical traditions of China, Spain, Brazil, and, above all, Japan. He knew a lot! But he never wanted to acknowledge Shakespeare. I think it was a kind of omertàfor him. But the work as a whole is truly a Shakespearean dream, like The Tempest.

M.G.: How did you first get to know the play?

M.D.: It was in Avignon in 1987. The show started in the late evening and lasted all through the night until the morning. I felt as if I'd been to the moon, or to Mars! I was one person going into the theater and another person coming out. In French theater, the tradition of the three unities is paramount—unity of place, unity of time, unity of action. Le Soulier de Satin takes place in Spain, Morocco, South America, Japan. It explodes every frontier.

M.G.: Did it cross your mind at the time that one day you would turn the play into an opera?

M.D.: Not at all. What struck me was that without music Claudel had already written an opera. The pathos of the lovers Don Rodrigue and Doña Prouèze is the pathos of characters you find in grand opera—or in the classical theater of Racine and Corneille. The very long sentences they speak create a flow that is closer to music than to dialogue. The length of the whole thing suspends time the way music does. The continuity never stops.

M.G.: Couldn't those "musical" properties get in a composer's way? I forget who it was who said that Shakespeare, being music already, could not be set to music.

M.D.: Yes, exactly! Yet composers have written beautiful music based on Shakespeare, which is encouraging for a composer working with Claudel! It's true that in creating the libretto, we had to cut a great deal. If you set the entire text of Le Soulier de Satin, the opera would last 24 hours! But we didn't need to. A lot of Claudel's language is there to suggest music. When you add music, you can strip such language away.

M.G.: Operas set in exotic locations—the Egypt of Aida, the Spain of Carmen, the Far East of Madama Butterfly and Turandot—often use unusual instruments or native melodies for local color. The story of Le Soulier de Satin takes us all around the planet. Does your score reflect that?

M.D.: At first, I thought about integrating ensembles from the Arab world and South America and Japan, but in the end I decided to stay with a traditionally European symphonic orchestra throughout, adding just a handful of unusual timbres, like the cimbalom, steel drums, and the Baroque guitar. I've quoted a bit of music from 17th-century Spain, also a choir from the monastery of Monserrat. But I'm less interested in "special effects" than in tradition and how you can disturb it. At one point, Claudel has a little ensemble playing onstage, and he says they should play very badly. Can you imagine asking the orchestra of the Opéra de Paris to play badly?

M.G.: Maybe the trick there would be to write the bad playing especially well!

M.D.: Exactly! To explore the idea.

M.G.: You made your name around the turn of the last century with instrumental music. But since Gesualdo, in 2010, you've been concentrating on opera. What changed?

M.D.: I started listening to opera when I was very young. I always wanted to write opera, but I had to wait a long time. My second opera was Charlotte Salomon, for the Salzburg Festival in 2014. And now Le Soulier de Satin, which I've been working on for five years.

Nothing is more complex than the emotion you feel at the opera. At a play you have an actor and a character, which creates a kind of vibration between what's real and what is illusion. But at the opera, a moment can touch you very deeply and you don't know why. Is it the character? Is it the singer? The voice? The melody? What's happening in the story? Those things are all tied up in a knot, and there's no way to untie it. Where does the emotion come from? It's a mystery. I'm trying to explore that.