Here's a recap of our playlist for August 26. Notes on our tracks for September 2 appear below the space break.

The history of our musical theater has few scandals to set beside that of the catch-as-catch-can unveiling of the Lefty agitprop vaudeville The Cradle Will Rock, book, lyrics, music, and orchestrations by Marc Blitzstein. Conceived in the spirit of the Threepenny Opera and produced by the federally funded Federal Theatre Project (those were the days!), the show nearly tanked at the eleventh hour, when Washington pulled the plug.

Little, however, had the bureaucrats reckoned with the grit of the producer John Houseman, the ensemble's guiding light—nor with the ingenuity and the moxie of the director Orson Welles, still wet behind the ears, the lighting designer Abe Feder, or Blitzstein himself, who marched the shut-out ticket holders from the shuttered theater to another house twenty blocks uptown, in the process doubling the size of their audience. So what if union rules barred the actors from performing onstage? They could improvise in the auditorium. So what if the rules barred the orchestra from playing in the pit? Who was to stop the composer from tickling the ivories beneath a rented proscenium? Swept up in the excitement, the Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and future Tony Award-winning playwright Archibald MacLeish leapt to the footlights for a post-performance panegyric.

That June evening in 1937 was high-water mark of guerilla theater, no doubt about it. Houseman gave his version of events in an introduction to a PBS telecast in 1985, around the time Welles was peddling a screenplay on the same subject. His version was never produced, but Tim Robbins wrote, directed, and produced his fictionalized Cradle Will Rock to acclaim in 1999. Blitzstein's show has seen dozens of productions, over the decades, one supposedly more triumphant than the next. How is it, then, that not even one of the nearly two dozen songs in the score has established itself as a standard? Something about this story simply fails to add up.

Well, last summer, Opera Saratoga took up the gauntlet, even exhuming the Blitzstein's orchestrations, unheard since rehearsals for the original production back in the day. John Mauceri, likely the composer's staunchest living champion, conducted. And now the live recording is out on Bridge.

From the promising titles on the songlist ("Honolulu," ""Hello, Doctor," "Order in the courtroom!"), Mauceri himself picked what he thought would be the three strongest tracks for our show. First, "The Rich" immediately followed by "Art for Art's Sake," together comprising the first-act finale, showcasting reptilian free-loading artistesand their snooty patroness Mrs. Mister. There are gags that land here and there, sure, but on balance, the satire galumphs. For a chaser, Mauceri suggested "Nickel Under the Foot," a sub-Brenchtian ballad for the downtrodden prostitute generically known as the Moll.

Mauceri, who listened in, suggested, in the most diplomatic of e-mails, that I might change my mind on the strength of the entire score. (It's not that long,.") Fair enough. Having checked it out, I remain unconvinced. Grant Blitzstein his a gift for names: the setting is Steeltown USA, the cast peopled by a Dr. Specialist, a Reverend Salvation, an Editor Daily, and the like, all cringing in the shadow of the tentacular Mr. Mister. But the social-industrial fable is a shambles, its moments of pathos as rote as they are unprepared. The orchestration has undeniable pizzazz, equal parts Weimar and Tin Pan Alley. The quotations that waft by ("...in the dawn's early light," "Rockabye baby...," a fanfare from Beethoven's Egmont overture, repurposed for the claxon Mrs. Mister's limousine) pique the ear. Past a promising initial flourish, the tunes tend to go nowhere at all. For my money, only the sister's lament for "Joe Worker" who got shafted begins to get under the skin. In fairness, the performance, largely entrusted to emerging talents from Opera Saratoga's Young Artist Program, is for the most part no better than sufficient unto the day. Ginger Costa-Jackson distinguishes herself as Moll, a more thankless role than it ought to be, and Matt Boehler has some fun as Mr. Mister. The all-too-copious spoken dialogue consists of wall-to-wall clichés, delivered with all the flair of drama-club regulars.

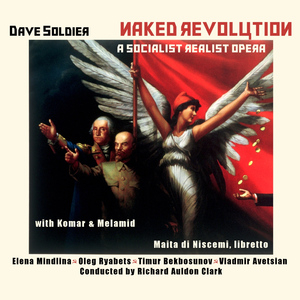

Next to prick up your ears: Naked Revolution: A Socialist Realist Opera from Immigrant Dreams by the polymath Dave Soldier, composer without borders and Columbia University brain researcher(on the Mulatta label). The libretto, by Maira di Niscemi (a new name to me), is every bit as hallucinatory as the subtitle suggests. Our first excerpt, "I was not my father's eldest son," involves George Washington, the head of George III as a Roman Emperor (eat your heart out, Manuel-Lin Miranda!), and a trio of slaves. In our second, "Lenin at Smolny Institute," the Bolshevik kingpin confronts the ghost of Tsar Alexander. And finally, in "Sing of nature," the dancer Isadora Duncan, free spirit of the floating scarves and the naked feet, raises her voice in revolutionary, heavily Slavic-accented song to the far-from-receptive Soviet Chairman. Move this swirling impasto, intriguing to the front of the queue.

Next to prick up your ears: Naked Revolution: A Socialist Realist Opera from Immigrant Dreams by the polymath Dave Soldier, composer without borders and Columbia University brain researcher(on the Mulatta label). The libretto, by Maira di Niscemi (a new name to me), is every bit as hallucinatory as the subtitle suggests. Our first excerpt, "I was not my father's eldest son," involves George Washington, the head of George III as a Roman Emperor (eat your heart out, Manuel-Lin Miranda!), and a trio of slaves. In our second, "Lenin at Smolny Institute," the Bolshevik kingpin confronts the ghost of Tsar Alexander. And finally, in "Sing of nature," the dancer Isadora Duncan, free spirit of the floating scarves and the naked feet, raises her voice in revolutionary, heavily Slavic-accented song to the far-from-receptive Soviet Chairman. Move this swirling impasto, intriguing to the front of the queue.

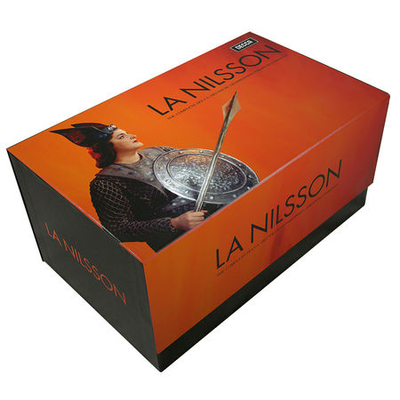

And to close, the conclusion of our celebration of Birgit Nilsson, consisting of a troika of tracks from Decca's massive compilation La Nilsson (Decca). "O don fatale," Princess Eboli's showstopper from Don Carlo, comes as the last of several surprises from Nilsson's Verdi album of 1962. I don't believe the lady ever appeared in the Spanish tragedy, and if she had, it's dollars to donuts she would have scorned the seconda prima donna part, by rights the property of a mezzo-soprano. And in truth, the low-pitched, slow middle section, awash in Eboli's pained self-pity at having done wrong, finds Nilsson way out of her wheelhouse, temperamentally no less than vocally. The convulsive self-reproach at the top of the aria, however, no less than the heroic resolve at the end unleashes her spirit in all its glory. Jump cut to Sieglinde's narrative "Der Männer Sippe," from Act 1 of Wagner's Die Walküre, panel two of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen, likewise a rarity. By comparison with the Valkyrie Brünnhilde, who dominates three of the cycle's four operas, the abused war bride Sieglinde is a brief role. As every Wagnerite knows, Nilsson ranks with the most thrilling Valkyries of all time. Nor was she however a stranger to the nominally lesser role, which is tremendous in its own right. It is instructive and deeply moving to hear her turn that light-saber soprano of hers to the intimate, tender, yet visionary back story Sieglinde tells here.

And to close, the conclusion of our celebration of Birgit Nilsson, consisting of a troika of tracks from Decca's massive compilation La Nilsson (Decca). "O don fatale," Princess Eboli's showstopper from Don Carlo, comes as the last of several surprises from Nilsson's Verdi album of 1962. I don't believe the lady ever appeared in the Spanish tragedy, and if she had, it's dollars to donuts she would have scorned the seconda prima donna part, by rights the property of a mezzo-soprano. And in truth, the low-pitched, slow middle section, awash in Eboli's pained self-pity at having done wrong, finds Nilsson way out of her wheelhouse, temperamentally no less than vocally. The convulsive self-reproach at the top of the aria, however, no less than the heroic resolve at the end unleashes her spirit in all its glory. Jump cut to Sieglinde's narrative "Der Männer Sippe," from Act 1 of Wagner's Die Walküre, panel two of Wagner's Der Ring des Nibelungen, likewise a rarity. By comparison with the Valkyrie Brünnhilde, who dominates three of the cycle's four operas, the abused war bride Sieglinde is a brief role. As every Wagnerite knows, Nilsson ranks with the most thrilling Valkyries of all time. Nor was she however a stranger to the nominally lesser role, which is tremendous in its own right. It is instructive and deeply moving to hear her turn that light-saber soprano of hers to the intimate, tender, yet visionary back story Sieglinde tells here.

And for our finale ultimo: the entrance aria of Puccini's bloodthirsty Turandot, "In questa reggia," joined in the final bars by her fellow sacred monster Franco Corelli as the unknown prince Calàf. (Of numerous recordings available, we chose the complete performance led by Erich Leinsdorf.) From Moscow to Milan to New York to Zurich, where I witnessed her in gale-force action while still in short pants, Nilsson's Chinese princess blew the figurative roof off theaters by the score with this music. In the long history of opera, there are few artists who can be said truly to have owned any role, but few, I think, would deny that Nilsson owned this one for all time.

Our selections for September, commentary capped for the hell of it at Twitter's bloated new limit of 280 characters.

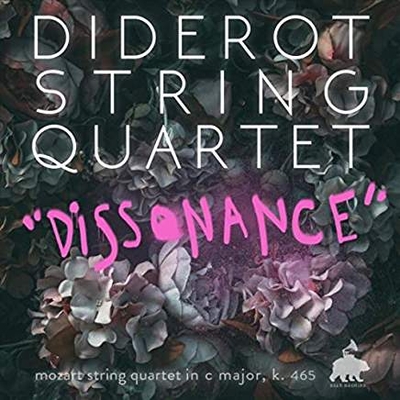

The opening movement, Adagio-Allegro, from the Mozart String Quartet No, 19 in C major, K. 465 ("Dissonance"), played by the Diderot String Quartet (on the Bear Machine label).

The opening movement, Adagio-Allegro, from the Mozart String Quartet No, 19 in C major, K. 465 ("Dissonance"), played by the Diderot String Quartet (on the Bear Machine label).

Young virtuosi thoroughly versed in the early-music aesthetic dive deep into the stringent, prophetic chromaticism of Mozart's one-of-a-kind introduction to this movement—and then cut loose in sheer joy. A bracing showing from the musicians, captured in all its vibrancy by a very close mike.

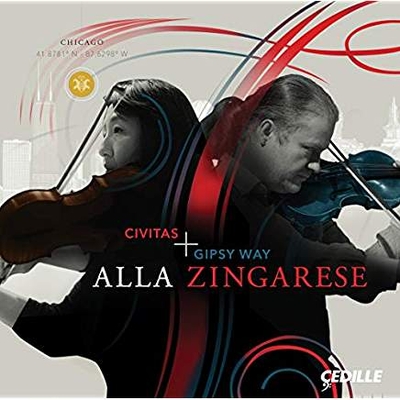

Johannes Brahms (arr. Lukaš Sommer), "Rondo alla zingarese" from the double album Alla Zingarese (Cédille), with the combined forces ofthe Chicago-based Civitas Ensemble, a Chicago-based chamber group, and the Gipsy Way Ensemble, from the Czech Republic, featuring a full house of native Roma musicians.

Johannes Brahms (arr. Lukaš Sommer), "Rondo alla zingarese" from the double album Alla Zingarese (Cédille), with the combined forces ofthe Chicago-based Civitas Ensemble, a Chicago-based chamber group, and the Gipsy Way Ensemble, from the Czech Republic, featuring a full house of native Roma musicians.

All the fire you hope for, all the spice you hope for, all the wayward moods and colors, minus all the nightclub hokum with which this thrice-familiar crowd-pleaser is typically encrusted.

Off Six Evolutions: Bach Cello Suites (Sony Classical), the Sarabande from Suite No. 5 in C minor, BWV 1011, and the Allemande from Suite No. 6 in D, SWV 1012, played by Yo-Yo Ma.

Off Six Evolutions: Bach Cello Suites (Sony Classical), the Sarabande from Suite No. 5 in C minor, BWV 1011, and the Allemande from Suite No. 6 in D, SWV 1012, played by Yo-Yo Ma.

At an earlier stage of his evolution, Yo-Yo Ma paired the cello suites with all manner of cinematic distractions. Here, he plays everything straight, proposing a schema of rising transcendence. The samples struck me as magisterial, marmoreal, and profoundly remote. Much heavy breathing.

From Ludwig van Beethoven: The Complete Piano Sonatas (Marquis), newly recorded by Stewart Goodyear, the third and final movement of Sonata No. 30 in E major, op. 109, marked "Gesangvoll, mit innigster Empfindung" (Songfully, with the most intimate expression).

From Ludwig van Beethoven: The Complete Piano Sonatas (Marquis), newly recorded by Stewart Goodyear, the third and final movement of Sonata No. 30 in E major, op. 109, marked "Gesangvoll, mit innigster Empfindung" (Songfully, with the most intimate expression).

Unlike his great precursor and fellow Torontonian Glenn Gould, Goodyear makes no fetish of eccentricity. His keys to this movement's mysterious theme and variations: pellucid touch, transparent textures, and an architect's instinct for proportion. Most promising.

And with a few extra minutes to spare, my top pick from The Cradle Will Rock: . "Joe Worker," in a gutsy rendition by Nina Spinner, a member of Opera Saratoga's Young Artist Program.

"How many frameups, how many shakedowns, /Lockouts, sellouts. /How many times machine guns tell the same old story. /Brother, does it take to make you wise?" Happy Labor Day!