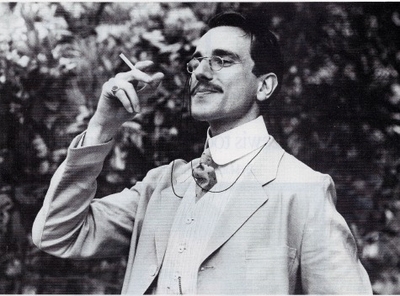

"Cecil," says E.M. Forster in the novel, "was mediæval. Like a Gothic statue. Tall and refined, with shoulders that seemed braced square by an effort of the will, and a head that was tilted a little higher than the usual level of vision, he resembled those fastidious saints who guard the portals of a French cathedral. Well educated, well endowed, and not deficient physically, he remained in the grip of a certain devil whom the modern world knows as self-consciousness, and whom the mediæval, with dimmer vision, worshipped as asceticism." On screen, in a first attempt to kiss his fiancée Lucy Honeychurch (Helena Bonham-Carter), Cecil comes to grief on his squashed pince-nez. Later, a chaste, stealthy second attempt is successful, and Cecil climbs the stairs to his bedroom, two steps at a time, with the sweet, self-contained joy and innocence of a bashful child. |

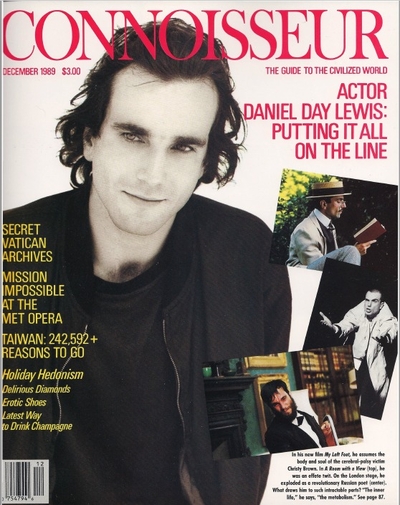

"I enjoy the process of physical change," Day-Lewis allows, touching the aspect of his masterly screen performances that has caused the most amazement. Since March 7, 1986, the day his first two major films opened in New York, his name has been a byword for a sort of versatility scarcely seen since the very dissimilar heyday of Alec Guinness. In My Beautiful Laundrette, with two-tone hair standing straight up, the gaunt young actor, then twenty-eight, played Johnny, a contemporary London street tough disenchanted with his dead-end way of life, strangely gallant, incidentally gay, and resolutely monosyllabic. In the Edwardian comedy of manners A Room with a View, preening and pomaded, he appeared as Cecil Vyse, aesthete, the heroine's absurdly articulate, ultimately rejected fiancé.

The contrast between the two flawless portrayals made them doubly striking. Day-Lewis was pronounced a "chameleon," a judgment that his next two films would not contradict. Fully clothed, disguised only by the purr and blurting cadences of a Czech accent, his Tomas, in The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1988), gave off the same erotic sheen as he did naked in the charged love scenes with his lustrous costars Juliette Binoche and Lena Olin. Next came his Henderson Dores, in the post-Waugh comedy Stars and Bars (1988), an art appraiser adrift in New York and a gothic South with nothing between him and panic but a splintering veneer of British propriety.

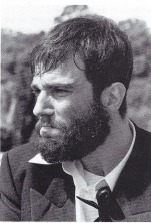

Even if an actor of Day-Lewis's ingenuity and address might, as he says, enjoy the process of physical change from each of these parts to the next, changing himself into Christy Brown for My Left Foot cannot have been other than agonizing. Much in the film is fictionalized, but the central fact is not. Christy Brown (1933-1981), the son of a Dublin bricklayer, was born a cripple, a victim of cerebral palsy, and written off by the doctors as a mental defective. His mother refused to believe them. At five, Christy gave his first sign of intelligence: he snatched a piece of chalk from his sister with his left foot. With his mother's encouragement, he painfully copied the letter A. From these beginnings he went on to paint, to learn to speak, and to write five books, including novels, poetry, and autobiography. Here, in Brown's own words, is a terrible epiphany of self-discovery at age ten:

"I looked at [my brother] Peter's hands. They werebrown, steady hands with strong, square fingers, hands that could clasp a hurley firmly or swing a chestnut high into the air. Then I looked down at my own. They were queer, twisted hands with bent, crooked fingers, hands that were never still, but which twitched and shook continually so that they looked more like two wriggling snakes than a pair of human hands. I began to hate the sight of those hands, the sight of my wobbly head and lop-sided mouth as I saw them in the mirror, so that I soon came to hate and fear a mirror. It told me too much. It let me see what other people saw every time they looked at me—that when I opened my mouth it slid sideways, making me look ugly and foolish, that when I tried to speak I only slobbered and gabbled, the saliva running down my chin at every word I attempted to say, that my head kept shaking and wobbling from side to side, that when I'd try to smile I'd only grimace and pucker up my eyes so that my face looked like an ugly mask. I was frightened at what I saw."

This exact image of horror, wrung from his able body, EI Greco hands, and sonneteer's face, is what Day-Lewis gave the camera. To find it, he spent eight weeks in a Dublin clinic working with children afflicted with cerebral palsy; to present it, he spent the six weeks on the set gnarled in a wheelchair, not eating unless others fed him, communicating in grunts. Surely it was a season in hell.

This exact image of horror, wrung from his able body, EI Greco hands, and sonneteer's face, is what Day-Lewis gave the camera. To find it, he spent eight weeks in a Dublin clinic working with children afflicted with cerebral palsy; to present it, he spent the six weeks on the set gnarled in a wheelchair, not eating unless others fed him, communicating in grunts. Surely it was a season in hell.

Of all the transformations the actor has undertaken, none has pushed him to such physical extremes as this. Coming when it does, and especially for viewers unacquainted with his work on the stage, the performance as Christy Brown inevitably raises the question whether Day-Lewis is not the very model of the actor of the suspicious second type: a genius at observation, a brilliant mimic, a cold-hearted wizard of surfaces. And that question in turn raises others. Who is behind those surfaces? What is he hiding? Why?

"It has been said that actors have no character," the French philosophe Denis Diderot wrote in his classic dialogue Paradox of the Actor, late in the eighteenth century, "because in playing all characters they lose the one nature gave them, that they become false in the way that the doctor, the surgeon, and the butcher become hard. I believe that the cause has been taken for the effect, and that they are suited to play all characters only because they have none of their own. "

That is true only in a world of epigram. The evidence, read it as we may, lies in every actor's life story. Day-Lewis's is a haunting one. In 1951, his father, Cecil Day-Lewis—a preacher's son, briefly a Communist, a poet, professor at Oxford, author of children's books and (under the pseudonym Nicholas Blake) highly regarded crime novels, future poet laureate of England—married the actress Jill Balcon, daughter of Sir Michael Balcon, production chief of Ealing Studios and discoverer of Alfred Hitchcock. It was the elder Day-Lewis's second marriage; he was close to fifty. The bride was twenty-six.

Daniel, who inherited his Russian-PolishJewish mother's black hair and green eyes, was the second of their two children and only son. Opposed to class conventions, his parents sent him to school first in working-class South London and later to Sevenoaks, one of those cold-shower-and-cricket establishments the British insist on calling "public," whence, at age twelve, he ran away to join his sister at the more progressive boarding school Bedales. There he began to take part in school plays. "What I loved about it most," he told an interviewer years later, "was the escape into another world." On another occasion, he phrased the matter differently: "It was a dark age, and the theater seemed to offer some light."

Christy Brown is to make an appearance at a benefit concert for cerebral palsy. A lively, pretty nurse has been assigned to take care of him backstage. Christy, who has never let his unprepossessing exterior stand in the way of a romantic infatuation, likes her looks, and likes her even better when she stands up to his grouchy bullying. The glint of amusement in his eyes is the prelude to a brave, whirlwind courtship. |

"I'm proud of my name and of my parents' achievements," he said as his films began to attract notice. "I don't think having famous parents has been a source of pressure for me. Much more I felt the pressure of having a father whom I didn't do a great deal to please. He was a kind and affectionate man, but remote, I suppose. I bitterly regretted not having achieved anything by the time he died. "

This spring, those remarks took on special resonance, when Day-Lewis assumed, with the National Theatre in London, the title role in Hamlet, the actor's Everest and a figure whose mission, couched in terms of revenge, is to give peace to his dead father's spirit. From all accounts, the premiere, in March, fell short of triumph. J. C. Trewin, a veteran drama critic, whose book Five & Eighty Hamlets covers productions of Shakespeare's tragedy from 1922 to 1987, among them those starring legends like Ernest Milton, John Gielgud, Laurence Olivier, and Paul Scofield, not to mention a host of lesser aspirants, wrote: "Through the night we are conscious that a full Hamlet, Prince of 'insoluble opposites,' is seeking to emerge, and that undoubtedly (for his actor is young) he will. I look forward to it." Five months later, Trewin had not been back for a second look but said privately, "He has all the potential required. He has the range and the strangeness that every Hamlet should have. But on opening night he hadn't yet lived himself into a real Hamlet. I felt he was on the outside looking in. I want to see him again, very much."

This spring, those remarks took on special resonance, when Day-Lewis assumed, with the National Theatre in London, the title role in Hamlet, the actor's Everest and a figure whose mission, couched in terms of revenge, is to give peace to his dead father's spirit. From all accounts, the premiere, in March, fell short of triumph. J. C. Trewin, a veteran drama critic, whose book Five & Eighty Hamlets covers productions of Shakespeare's tragedy from 1922 to 1987, among them those starring legends like Ernest Milton, John Gielgud, Laurence Olivier, and Paul Scofield, not to mention a host of lesser aspirants, wrote: "Through the night we are conscious that a full Hamlet, Prince of 'insoluble opposites,' is seeking to emerge, and that undoubtedly (for his actor is young) he will. I look forward to it." Five months later, Trewin had not been back for a second look but said privately, "He has all the potential required. He has the range and the strangeness that every Hamlet should have. But on opening night he hadn't yet lived himself into a real Hamlet. I felt he was on the outside looking in. I want to see him again, very much."

Whether or not it would have convinced him more, the Hamlet Trewin could have seen in August was indeed strange. The production, by the National Theatre's new director Richard Eyre, was conspicuous mostly for its indebtedness in decor and tone to old-fashioned Romantic tradition. The choice, one must suppose, followed from the casting of the prince. "It's rare," Eyre notes, "to have a Hamlet who fulfills Ophelia's description of the character: 'The courtier's, soldier's, scholar's, eye, tongue, sword,/Th'expectancy and rose of the fair state'/The glass of fashion and the mould of forrn. Th' observed of all observers.' It's quite utopian."

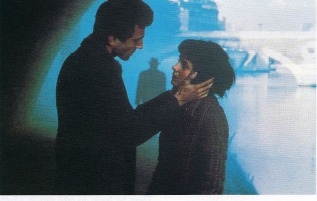

"Take off your clothes," says the womanizing brain surgeon Tomas in the film's opening line. The husky, suave command brings to mind a passage from Milan Kundera's original novel: "Tereza knew what happens during the moment love is born: the woman cannot resist the voice calling forth her terrified soul; the man cannot resist the woman whose soul thus responds to his voice." Elsewhere in the book, the artist Sabina, one of his mistresses (Lena Olin), tells Tomas, "You seem to be turning into the theme of my paintings. The meeting of two worlds. A double exposure. Showing through the outline of Tomas the libertine, incredibly, the face of a romantic lover. Or, the other way, through a Tristan, always thinking of his Tereza, I see the beautiful, betrayed world of the libertine." In the film, the point is made when Tomas rejoins his wife, Tereza (Julliette Binoche), in Prague after the Soviet invasion. At his knock she opens their door and sees not the peremptory seducer she has always known but the Tristan, drawn, stony, solemn, terminally sick at heart. |

But then he spoke, and plunged into a concerto. Henceforward the other voices would be the orchestra; Hamlet's—deep, rolling, bold, like a cello, splendid in antagonism, yet lyric—the solo. Not bound by the sense of the words, its cantilenas, its roars, its occasional tortured squeaks made incantatory music of their own. Through the evening the face, so striking from the start, kept up a parallel, mute discourse, romantically somber for the most part but always capable of startling change, screwed for the Ghost scenes into a mask of gothic horror, lit with a furtive, heart-breaking smile seconds before the grimace of the final agony. A florid choreography of gesture—fluent arabesques for the hands, slow-motion whole-body contortions on the floor, prancing bursts of balletic lunacy, blue-ribbon fencing—unfurled a third, independent layer of expression. What the effects of face, voice, and gesture all added up to was unforgettable, beyond summary, and yet stubbornly elusive.

"Dan is a very idiosyncratic actor," says Judi Dench, who as Hamlet's mother, Gertrude, shared with Day-Lewis the Closet scene. That, you recall, is the violent sequence, beloved of Freudians, where the queen ("her husband's brother's wife"), in collusion with her son's enemies, undertakes to dress Hamlet down for his spiraling hostility and aggression. But Hamlet instantly turns the tables, and by the time he leaves her, reconciled to him and contrite at her second marriage, her son has put her in fear of her life, run the eaves-dropping councillor Polonius through with his sword, and fallen into a ghastly colloquy with his father's ghost, which Gertrude neither hears nor sees. No other confrontation in the play struck such sparks, and it ended even more shockingly, on a long, lingering kiss.

"Hamlet for most actors is a very private role," Dench continues. "For Dan, in a way, it's a way of life. It's an extremely private life. Everything changes ever so slightly each evening, which is wonderful—but in that role he's very self-absorbed. He'll laugh and joke before the play, but once it starts, he goes straight through. You never know in your scenes with him what you'll be taking on. It's disturbing—in the best possible way."

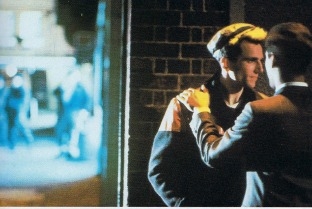

Johnny, a street tough of South London, is minding the store for Omar (Gordon Warnecke, back to camera), an old Pakistani school pal, when Salim, Omar's slick, drug-dealing cousin, drops in on business. Johnny does not talk much (his longest speech is barely four lines), but when Salim asks, "Is it worth waiting?" Johnny answers with a flash of controlled ferocity that betrays contempt for Salim's rackets, reckless love for Omar, and the disgusted knowledge that Omar is on the edge of turning into a junior Salim—all in the sentence, "In my experience it's always worth waiting for Omo." |

There is, he insists, "absolutely no difference" creating a performance for theater or for film. Either way, the heart of the matter is the same: that discovery. Day-Lewis, it turns out, works neither from the inside out nor from the outside in. He gives himself over. "I have a perverse desire for self-oblivion," he says, his haunting voice tinged with melancholia. "That's what I most long for in my work.

"I'm perversely drawn to roles that are impenetrable for me. I'm attracted to people at some distance from my own life and other characters I've done. You can see the process as being a lifetime of infidelities. We choose to restrict ourselves by external things--clothes, appearances in every walk of life. I prefer the exhilarating fear that there is in accepting that we have ... not endless possibilities, but certainly many that remain unexplored, more than we ever dream."

To cross the lobby of Atlanta's Monopark 5000 to the elevators, one goes by canoe, a craft with which the British art appraiser Henderson Dores is unfamiliar. Farcical mishaps abound (watch for the floating eagle totem), and beneath his chipper, hopeless exterior roils a maelstrom of existential panic. Though it flopped, this comedy is an oddball gem. |

Testing his film performances—so memorable and so various—against the implied standard of authenticity, one sees that the initial reaction to Day-Lewis's virtuosity completely missed the mark. With a true chameleon's outside-in job, Day-Lewis's impersonations have nothing in common. It is not his conversation that tells us so but what is up on the screen.

Compare, for contrast, Dustin Hoffman's autistic Raymond, in Rain Man. Raymond's tics are not keys to his character; they are all there is. Set his dead, unchanging eyes against Day-Lewis's Christy Brown's, so full of suspicion, mischief, purpose, rage, and joy. Whenever we think we have figured Christy out, there is a subtle flash of something unsuspected. No matter how difficult the character, Day-Lewis bestows on him a gift of empathy, of imaginative understanding. Intellectual analysis has something to do with it, but not much. The secret is loyalty. He never wavers in his acceptance of the person he has consented to become. He imposes no theory, he offers no comment, and he never withdraws his affection.

"I most enjoy the loss of the self," Day-Lewis says, assessing the satisfactions of his work. "That can only be achieved through detailed understanding of another life—not by limping and growing a mustache.

"Great acting has nothing to do with acting! Think of Montgomery Clift. I have no idea what he was like as an actor, but on-screen, there is a palpable cry for help—nothing to do with self-pity, but there was a need that he had. You wanted to reciprocate, fill the void for him. For me, great acting has nothing to do with acting whatsoever. It's to do with people being generous with themselves."

It sounds, if not like penance, like atonement. The generosity, one begins to understand, flows first of all to the characters he plays and only incidentally to the spectator. And the characters he chooses are voracious. Asked in August if he was feeling wistful at the prospect of giving up the part of Hamlet, he said no. "When I have performances of that dreaded play," he explained, midway through a week with five, "it takes three-quarters of the day to clear my eyes. This has certainly taken me closer to the abyss than anything else. And I've discovered fears in myself, or generated fears, I never knew before—and once they're there, they're very difficult to put away again." At the tail end of the run, in September, those fears seem to have gotten the better of him. He withdrew from the play in mid-performance, with only seven more shows to go. The London papers cited "nervous exhaustion." Patently, he had given too much. No matter what the project, says Richard Eyre, who directed Day-Lewis on two occasions prior to Hamlet, the actor gives it "his whole heart, mind, and body." The prototypical British actor may revel in playing three contrasting roles in rotating repertory plus perhaps a film or television part on days off (here are the chameleons); not Day-Lewis. "I'm really uncomfortable dividing my attention," he says. "I couldn't do rep anymore, but it's a luxury concentrating on one thing at a time. I chose it long ago, even if it meant I had to be out of work. Sometimes there was nothing at all. I wasn't always faced with an embarrassment of choice."

Still in thrall to one role, what role he might take next is a subject he cannot consider. "At the end of every project, I say, This is the last time I'll lend my life to another life. But there is an impulse that miraculously renews itself."

Such miracles only befall an artist who befriends his demons.