Ever elegant: Yveta Synek Graff, of upper Park Avenue and citizen of the world. |

Yveta Synek Graff died at her home in Casa Dorinda, Montecito, California, on November 6. Born in Prague, Czechoslovakia, on November 18, 1932, Yveta was the only child of the distinguished judge, author, playwright, editor, politician, and diplomat Emil Synek and Eugenia Budlovska, formerly a star of Czech theater. Wanted by the Nazis, Synek escaped to Western Europe in 1939 and spent the following years chiefly in England, serving under President Edvard Beneš in the Czechoslovak government-in-exile. His wife and daughter endured the hardships and anxieties of World War II in Podolí, on the outskirts of Prague, totally in the dark about his fate. At war's end, he caught the first train back to Prague,. In 1947, anticipating the imminent Communist takeover, he spirited himself and his wife and daughter to Paris.

Forgotten but not gone? In School for Love, one Yva Synkova appeared briefly as Mme Lukas. |

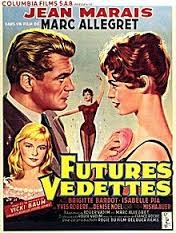

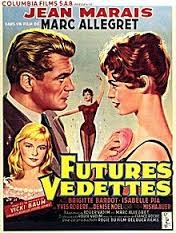

By her own account, Yveta lived a charmed life, never driven by ambition but always blessed with good luck. She flourished in Paris, where she began to study voice with Ninon Vallin, a leading French soprano of the prewar generation. At the same time, she enjoyed to the full the social whirl and traveled extensively with her parents. At a charity ball, she won the grand prize: a spanking new American automobile. As Miss Kodak, she modeled in promotional campaigns that splashed her face across billboards throughout France. The film director Marc Allegret cast her in a supporting role in

Futures Vedettes ("School for Love"), starring Jean Marais and Brigitte Bardot.

"I like to have fun." Young Yveta in a carefree mood, undated. |

Midway through the 1950s, Yveta ran into a top U.S. State Department official at a party in Geneva. "Why aren't you in America?" he asked. "You'd never give me a visa," she replied. She returned to Paris to find a telegram inviting her to the American embassy to process the paperwork. And so, in the summer of 1956, she set out for the New World, fulfilling the dream of her whole European generation. Aboard the Île de France, she dined at the captain's table and was promptly "adopted" by the assistant to the general manager of the Metropolitan Opera, gaining unrestricted entrée to rehearsals and performances before setting foot on American soil.

Her first winter in New York, Yveta met the children's fashion designer Robert Lincoln Love on a ski lift in Vermont and eloped with him to Las Vegas. The newlyweds settled on a high floor at 1120 Park Avenue in Manhattan, which was to remain Yveta's home for 45 years. Two sons—Steve and Brett—were born of the marriage, which ended in divorce.

In 1973, Yveta married F. Malcolm Graff, a private banker with Bankers Trust. A classic blonde beauty in the Eastern European mold, always impeccably turned out by George Stavropoulos, couturier to the likes of Elizabeth Taylor and Barbra Streisand, Yveta was a staple of the society pages. But Graff, in tandem with Yveta's formidable father, pushed her to but her enterprise and intelligence to better use. Having received from an uncle in Prague the score of Smetana's Dalibor—as it were a Czech Fidelio, unknown beyond Czech borders—she brought it to Eve Queler of Opera Orchestra of New York. With Yveta's advice and hands-on assistance every step of the way (she even marked the bowings in the string parts), a concert performance at Carnegie Hall resulted in 1977. With it, the stage was set for Yveta's ensuing campaign as the ambassador of Czech opera worldwide.

Before Yveta, Czech opera on international stages began and ended with Smetana's The Bartered Bride, plus the rare mounting of a Janáček opera, usually in Germany or (even in America) in German translation ill matched to the music. Through Yveta's dedication, Jenůfa, such other Janáček masterpieces as From the House of the Dead, The Cunning Little Vixen, Káťa Kabanová, and The Makropulos Case, and Dvořák's Rusalka have become repertory staples in capitals from New York, San Francisco, Seattle, and Chicago to London, Paris, and beyond.

Under Yveta's tutelage, Dvořák's water sprite Rusalka became a breakout role (perhaps the breakout role) for a most-favored protégée, Renée Fleming, Photo: Ken Howard. |

Yveta waged her tireless one-woman international campaign until well into the new century. For opera companies not yet ready to take on the challenge of Janáček in the original, she prepared, together with her colleague and editor Robert T. Jones, idiomatic, rhythmically scrupulous singing translations in American English; Leonard Bernstein judged her

From the House of the Dead for the New York Philharmonic "perfect." For international singers without Czech, she transliterated Czech scores syllable by syllable in a simple, efficient system of her own devising, also providing word-for-word translations. The greatest seeming gap in her life's work—the absence of an English

Rusalka—is easily explained. Unlike the Janáček operas, the Dvořák fairy tale, which Yveta worked on in nearly a score of international productions, is set to a self-consciously literary libretto by Jaroslav Kvapil, in verse, with rhymes. She deemed his poetry untranslatable.

Yveta's pointedly American translation of The Cunning Little Vixen won over UK audiences, too. |

Yveta's services were rendered in what she called her "package deal," which typically included program notes (written and/or spoken) and the novelty of supertitles. Eminent directors relied on Yveta to hone the drama of Czech operas moment to moment; Gian Carlo Menotti opined that she should direct on her own. In musical matters, Yveta acted as right hand to such maestros as Rafael Kubelik and Sir Charles Mackerras. And she coached stars like Renée Fleming, Karita Mattila, Catherine Malfitano, Patricia Racette, Dolora Zajick, and Brandon Jovanovich—not to mention every member of every supporting cast—to resounding triumphs. When artists came to her, even a youngster still at Juilliard with dreams of performing Janáček's

Diary of One Who Vanished on his final recital, she could not say no. Over the decades her example spawned a whole generation of artists, coaches, and accompanists steeped in Czech repertoire. Indeed, Yveta's influence may have extended further. Intrigued by Janáček's renowned sensitivity to the inflections of spoken language, Philip Glass consulted Yveta on his technique of setting words to music.

Role model? Catherine Malfitano gave a bravura performance as Emilia Marty in The Makropulos Case, coached by Yveta, who at times identified with the 337-year-ol diva and repository of arcana. |

Through 1988, Yveta's partnership with Opera Orchestra of New York yielded a landmark string of five Czech operas in all. But of all her institutional associations, none was a greater source of pride to her than the one with the Metropolitan Opera, where she served as de facto subject-matter expert in all matters Czech for over two decades, beginning with the

Jenůfa revival of 1985, sung in the Synek-Graff/Jones translation. Reporting for work on the company premiere of

Káťa Kabanová five years later, she was handed the key to room 210, her personal studio until her valedictory Met "Rusalka" in 2009. The

Jenůfa revival of 1992, with incendiary performances by a multinational cast including Gabriela Beňačková, Leonie Rysanek, Ben Heppner, and Jacque Trussel, under the baton of James Conlon, counts as a watershed in the operatic history: proof positive that Czech opera in the original was no provincial specialty, but an integral and indispensable part of the international repertoire. Yveta had won her case.

Yveta's passion for Czech opera was an inspiration also to visual artists, like Maurice Sendak. |

Like Yveta's parents, she and Malcolm were enthusiastic world travelers. Between assignments, they would recharge in exotic locations from Fiji to Zihuantejo, the Turks and Caicos to Moscow, Phuket to Hong Kong. They treasured life with Yveta's sons and their families, as well as with their godson Marc Chazaud. Malcolm died in 2013.

Devoted as she was to her adopted United States, Yveta also maintained close ties with émigré compatriots like Jarmila Novotná, the Met diva of yesteryear, and Rudolf Firkušný, the distinguished concert pianist. And it was not until her very last years that a Christmas would pass without the traditional Christmas goose, personally prepared by Yveta.

Her services to Czech opera transcended politics. From the hands of Communist officialdom and after the Velvet Revolution from Václav Havel, the first democratically elected Czech president in more than four decades, she received every award her home country had to bestow, among them medals named for Dvořák , Smetana, and Janáček. Her rare visits to her native city invariably escalated to state occasions, with abundant honors and press coverage. Transliterations of hers were published by G. Schirmer in the anthology series "The Diction Coach" as well as by Universal Edition in a new edition of Jenůfa.

In 2009, the Graffs retired to Santa Barbara, where the Music Academy of the West invited her to prepare a concert performance of the demanding second act of Jenůfa. With the inauguration of the Yveta Synek Graff Czech Opera Collection at The Juilliard School's Lila Acheson Wallace Library in 2012, complete with an invitational concert of Czech songs, Yveta reached a formal close to her remarkable career. The working scores, notes, production photographs, and rare books in her archive represent a rich resource for future performers and scholars.

Yveta is survived by her son, Steve Love, his wife, Jeanie Love, her grandson, Chase Love and her god-son, Marc Chazaud.