S alome, move over. In Written on Skin, an adulteress feeds on her lover's heart. George Benjamin's second opera derives from the — let's hope apocryphal — vita of the thirteenth-century troubadour Guillem de Cabestany, recycled by Boccaccio a century later in The Decameron (day four, tale nine). Benjamin's version sets a mock-narrative "text" by Martin Crimp, who presents the action as seen (and in part reenacted) by a squadron of present-day angels, casually conversant with car parks, the Holocaust, pornography and frequent-flyer miles.

alome, move over. In Written on Skin, an adulteress feeds on her lover's heart. George Benjamin's second opera derives from the — let's hope apocryphal — vita of the thirteenth-century troubadour Guillem de Cabestany, recycled by Boccaccio a century later in The Decameron (day four, tale nine). Benjamin's version sets a mock-narrative "text" by Martin Crimp, who presents the action as seen (and in part reenacted) by a squadron of present-day angels, casually conversant with car parks, the Holocaust, pornography and frequent-flyer miles.

Now in his early fifties, Benjamin continues to enjoy the rock-star status thrust upon him in his teens, though his catalogue remains compact. Poobahs at the Festival d'Aix-en-Provence premiere in July 2012 debated whether the ninety-minute Written on Skin — his most expansive score to date — was the greatest opera since Wozzeck or merely the greatest of the past twenty years.

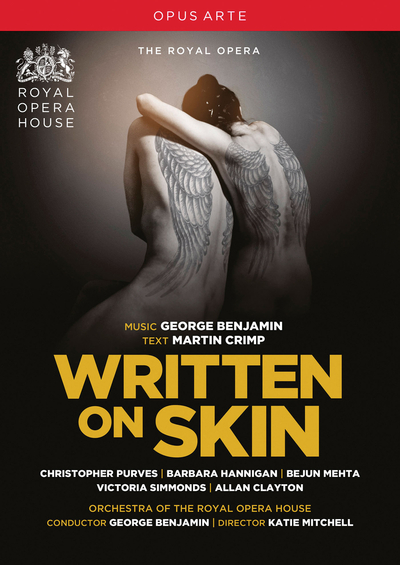

The video from the Royal Opera House, taped eight months later, showcases the principals of the premiere. As in Aix, the composer is on the podium, and Katie Mitchell's icy, high-tech original production — spread over interconnecting compartments on split levels — runs its infernal course like a well-oiled killing machine.

Though the subject might justify gale-force Expressionism, Benjamin finds subtler means to jangle the nerves. In addition to the standard symphonic complement, his orchestra incorporates a bass viola da gamba, a glass harmonica, bongos, a computer keyboard (or typewriter) and two pebbles. Everything but the kitchen sink, you might say, yet Benjamin works with fastidious nuance, layering transparent soundscapes that unfold in somber radiance.

The vocal writing for the most part feels intimate and conversational. Christopher Purves voices the domestic tyrant known as the Protector the way Michael Gambon reads Beckett, tracing fissures in a disintegrating soul. As the Boy, hired to glorify the Protector's earthly paradise in words and pictures on parchment (these are what is "written on skin"), Bejun Mehta touches chords of the unearthly.

Appropriately so, for the Boy is the emanation of the opera's principal time-traveling angel. More mesmerizing still, Barbara Hannigan's Agnès displays a fawnlike persona that belies the maelstrom within. From sex-starved pawn to unrepentant monster, the character travels an arc as wide as Kundry's. Hannigan's rounded, lyrical soprano makes music even of her most jagged lines, clear up to a sustained, climactic "scream" on high C.

In the final pages of Written on Skin, we hear of the angels' "cold fascination for human disaster." Indeed. For all its art, this is a hard work to warm to. In its hint of experience agonizingly inscribed on living flesh, the title calls to mind Franz Kafka's horror story In the Penal Colony (the source of the jittery chamber opera by Philip Glass, a masterpiece). Repasts of human flesh, dished up from hubris or for revenge, put it in the unholy company of the House of Atreus, Shakespeare's Titus Andronicus, Stephen Sondheim's Sweeney Todd, and Peter Greenaway's lurid The Cook, the Thief, His Wife, & Her Lover. With Martin McDonagh's bone-chilling tour de force The Pillowman, Written on Skin shares a clinical, not to say psychopathic, detachment in the face of nightmare.

And then there is Agnès, a diabolical double of Molière's indomitable teenager of the same name. Convent-bred for the marriage bed of an old buffoon, Molière's Agnès thwarts her "protector," obeying instinct, curiosity, appetite. For the duped Arnulphe, The School for Wives is a tragedy. For Agnès, it's a lark. In Written on Skin there are only losers. The brutally asymmetric battle of the sexes rages on. Why not call it war?