In a program note for the original production of Dionysos, documented on this new release from Unitel, the composer/librettist Wolfgang Rihm touched on elements of the comic that automatically arise when mythical characters are projected on historical ones, however tragic their destinies. "I picture Laurel and Hardy at the edge of a high-rise roof," he noted parenthetically, "gripped by the fear of falling."

Dionysos operates on the very principle Rihm describes. His libretto consists entirely of words and phrases from the thinker and poet Friedrich Nietzsche's late Dionysos-Dithyramben, oracular jottings set down on the verge of his descent into madness and silence.As "dialogue," Nietzsche's language lends a weight of archetype to the wisps of biography hinted at in the stage action. (To speak of plot would be a stretch.) But Laurel and Hardy? I don't think so.

The principal characters are three — a baritone protagonist known as N., a soprano intermittently called Ariadne, and a tenor doppelgänger introduced as A Guest but later unmasked as Apollo. It comes in handy to know that Nietzsche identified with Dionysos, the Greeks' anarchic god of inspirational abandon, and that Ariadne was Nietzsche's pet name for Richard Wagner's wife Cosima, with whom he was in love. In a harrowing finale, N./Dionysus morphs into Marsyas, the satyr Apollo bested in a music contest and then flayed alive. To drive home the horror, a dancer embodies the Skin, which continues to suffer and does not die.

Beginning with the sound of women laughing, the score quickly devolves into a maximalist post-Romantic fresco of oceanic variety. Gossamer instrumental episodes find a place, as do violent eruptions from the chorus, a hymn here, a waltz there, spells of limpid melody, not to mention the tortured vocal arabesques without which no high-modernist magnum opus is complete.

Conducting without baton, Ingo Metzmacher, who lives for such challenges as this score presents, has every whisper and thunderclap at his eloquent fingertips. As for Rihm's merciless writing for the voice, the superlative cast confronts the demands unfazed. Solo but also frequently in tandem, Johannes Martin Kränzle, as N., and Matthias Klink, in the dual tenor part, perform flawlessly in modes both lyric and heroic. Mojca Erdmann nails Ariadne's flights into the stratosphere with chilly instrumental authority, a feat for which not all listeners may thank her.

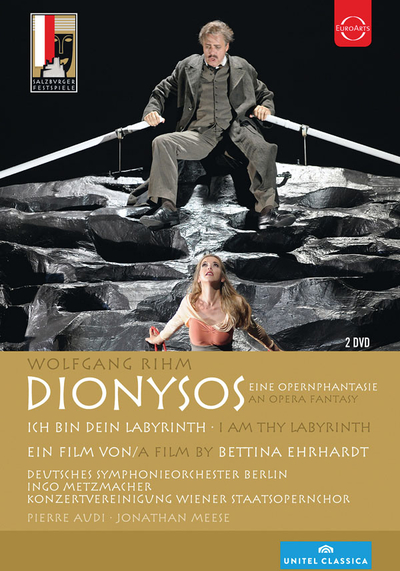

I remember the unveiling of Dionysos at the Salzburg Festival 2010 as a triumph unmarred by a single boo. That said, the triumph belonged not to the musicians alone. Pierre Audi directed, but what stuck in the mind were the antic, antirealistic designs by painter Jonathan Meese. For N.'s rowboat on Lake Lucerne, Meese built a mound of frozen waves, surmounted by a pair of oars. For the Alps, he brought on a jumble of pyramids and a ladder.

Vivid though these images remain in my mind's eye, they look flat and flimsy and go for nothing as shot by video director Bettina Ehrhardt. By the same token, the excellent projections by Martin Eidenberger and lighting by Jean Kalman vanish virtually without a trace. Apart from briefly glimpsed totemic wild-animal and earth-mother outfits, Jorge Jara's costumes look unaccountably woebegone. Not much of the acting survives the excessive close-ups. (Erdmann in particular might want to sue.) Footage of the offstage chorus serves no purpose, but I make no complaint about glimpses of Metzmacher on the podium, shaping even the most volcanic passages with unequaled serenity and grace.

In truth, a CD would make a better case for Dionysos than this inept video; Ehrhardt's dutiful fifty-three-minute documentary I Am Thy Labyrinth, a "bonus," in no way tips the scale.