Brains, beauty, a billion dollars—the tobacco heiress Doris Duke had all these, and headaches to go with them. As her half-brother and frequent travel companion Walker Patterson Inman once said: "Everywhere we go, it's the same. She gets to see a few of the sights, goes out to dinner a few times, and then her identity becomes known and we have to rush off somewhere else. We can't take any chances. When word gets out that she's in town, it's like telling gangsters: 'Here's a lot of money. Come and get it.'"

Born in 1912, Duke died just shy of her 81st birthday in 1993. Obituaries ticked off the death of her self-made father when she was 12; her subsequent lawsuit against her mother to block the sale of his real estate; two (or three) brief marriages she paid through the nose to terminate on grounds of extreme mental cruelty; a daughter, Arden, who lived but a day; a "freak" auto accident resulting in the death of an interior decorator crushed against the gate of one of her mansions (Duke was at the wheel); her falling out with Chandi, the 35-year-old Hare Krishna disciple she adopted as her daughter in old age. Duke's lifelong largesse to education, medical research, the arts, the environment and other philanthropic causes, perpetuated by lavish bequests, rated fewer column inches. In fairness, the New York Times did cite her support in areas from "animal rights to AIDS, historical preservation to orchids."

Try as Duke might to guard her privacy, word got out. There were reportedly many lovers, among them the celluloid swashbuckler Errol Flynn, Gen. George S. Patton, and the surfing legend Duke Kahanamoku. She once posted bail ($5 million) for her dear friend Imelda Marcos. In 2006, HBO aired "Bernard and Doris," a sad, sad feature-length chronicle of her final years under the eagle eye of Bernard Lafferty, the Machiavellian, alcoholic Irish butler who was to become her executor. Susan Sarandon and Ralph Fiennes took the title roles. Lauren Bacall and Richard Chamberlain had already enacted this sordid chapter in 1999 for the CBS miniseries "Too Rich: The Secret Life of Doris Duke," which also starred Lindsay Frost as Duke ages 20 to 50, and Hayden Panettiere, currently starring in "Nashville," as young Doris.

Duke was a woman of many talents. She spoke fluent French, played the piano, baked fine whole-wheat bread, filed wire dispatches from postwar Rome, and surfed at the championship level. Yet her greatest talent may have lain in the art of cultivating personal oases: inherited manor houses in rural New Jersey and in Newport, R.I.; Falcon Lair, in Beverly Hills, Calif., once the home of Rudolph Valentino; a Park Avenue penthouse; and the flying bedroom in her private Boeing 737. But the most remarkable of them all was the Xanadu that Duke built from the ground up at Kupikipikio, a remote spit of land on Maunalua Bay by the foot of the extinct volcano Diamond Head. On a seawall below, voices lost to the wind and waves, locals swam and fished, the same as for untold generations and even today.

An architectural fantasia on Islamic motifs and at the same time a tribute to the relaxed spirit of the islands, it perches above the breakers of the Pacific like an ark from another world: out of its element, yet perfectly at home. Jewellike colors, intricate patterns, light filtered through leaves and carved screens and vibrant chunks of tinted glass, tiled rooms and lush gardens combine in a single flow. If her other properties reflected the life Duke was born into, this one expressed the life she had chosen. Cecil Beaton, one of only four photographers to shoot the place during Duke's lifetime, called it a "really fabulous Arabian Nights Dream Persian House."

Duke called it Shangri La.

Its doors have been open to the public since 2002.

"That's it?," a tourist asked recently, pulling into the banyan-shaded courtyard. True enough, the exterior, in classic Arab fashion, is deliberately unimpressive. A long white wall, a single carved door flanking a pair of Chinese camels from Gump's, in San Francisco, give nothing away of the splendors within.

Like Captain Cook, Duke discovered Hawaii while circumnavigating the globe. The year was 1935, and she was on her honeymoon, the 22-year-old bride of the political hopeful James H.R. Cromwell, 38, a scion of yachtsmen, author of a tendentious, long-forgotten volume entitled "The Voice of Young America."

In transit since February, the newlyweds alighted in Honolulu in August. The quick layover they had planned stretched out to four months. The oceanfront parcel was purchased in 1936; construction of the house began the same year. On Christmas 1938, the Cromwells moved into the Mughal Suite, a custom-built inlaid-marble master bedroom and bath inspired by the Taj Mahal. Other early acquisitions included some 900 rare polychrome flowered tiles from the ancient Turkish ceramic center of Iznik, commissioned furniture, screens, a ceiling from Morocco, a 13th-century prayer niche from Iran, and a glazed goodie or two from the private collection of William Randolph Hearst. Duke made a final major purchase for the collection, a large mosaic tile panel, one year before she died.

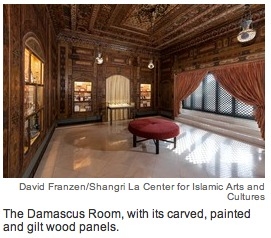

In the tropical sunshine and ocean spray, upkeep is never-ending. Last year, Shangri La made headlines with the opening of the Damascus Room, a meticulously orchestrated ensemble of carved, painted and gilt wood panels—some original, some new—in the late Ottoman style. The restoration of the Mughal Suite, as yet known to the public only from photographs, promises to wrap about a year from now.

No mere mausoleum to faded celebrity, the complex operates today, per Duke's will, as a center for Islamic arts and cultures, offering guided tours, residencies for scholars and artists, and programs that aim to improve understanding of the Islamic world, a world Duke had come to cherish on her travels for its art and its gracious hospitality. No doctrinal agenda is apparent. A glistening tile prayer niche from the tomb of Imamzada Yahya at Veramin, Iran, for instance, serves here simply as a thing of beauty, a joy forever.

Shangri La continued to evolve throughout Duke's life. The original theme for an intimate dining room overlooking the water was predictably marine, complete with built-in aquariums. But as her vision of a permanent center for Islamic study took hold, Duke draped the interior in 453 yards of custom-woven, blue-striped Indian fabric. Presto: The royal tent of a desert chieftain, pitched on sands of the imagination.