On MySpace carving out a virtual niche of your own takes a few clicks of a mouse. In the real world the job never ends. As classical divas at the head of the class Cecilia Bartoli and Renée Fleming share native talent, personal glamour, a puritan work ethic, a capacity for self-criticism and also something extra: a scholar's taste for intellectual adventure.

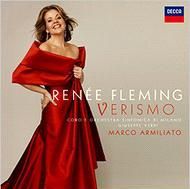

Long evident in their discographies, these attributes shine again in their latest recordings, both for Decca. Ms. Fleming's "Verismo" and Ms. Bartoli's "Sacrificium" are like graduate seminars dressed up as recitals.

Long evident in their discographies, these attributes shine again in their latest recordings, both for Decca. Ms. Fleming's "Verismo" and Ms. Bartoli's "Sacrificium" are like graduate seminars dressed up as recitals.

Ms. Fleming, 50, recalls the advice given her by Herbert Breslin, who masterminded Luciano Pavarotti's career. " 'You won't make it if you don't sing bread-and-butter Italian opera,' he told me," Ms. Fleming said in a recent telephone interview. "I was constantly being pushed toward a European ideal of what it means to be a classical or opera singer, let's say in the Renata Tebaldi mode. I reject that. I'm American. I'm eclectic. I'm going to follow my musical passions. And if people don't like it, and it hurts my legacy, I'm not going to worry about that."

The late 19th century and the first quarter of the 20th have proved particularly congenial to Ms. Fleming's gifts. In 2006 she surveyed that period on "Homage: The Age of the Diva," recorded in St. Petersburg, Russia, with Valery Gergiev leading the Orchestra of the Maryinsky Theater. Inspired by historic recordings of stars like Mary Garden, Maria Jeritza, Rosa Ponselle, Emmy Destinn and Lotte Lehmann, the program included a sprinkling of favorites among a spate of rediscoveries.

"I don't like to repeat things very much," Ms. Fleming said. "The minute something becomes familiar, it becomes difficult. I start to make up problems or vocal issues. Being steeped in the process of learning and exploring keeps me from becoming too nervous. Partly it's about not getting bored."

In "Verismo," featuring the Orchestra Sinfonica di Milano Giuseppe Verdi conducted by Marco Armiliato, she concentrates on the "young school" of Italians who followed in the wake of Verdi. Balancing 7 tracks by the grand master Puccini (including a few obvious choices) are 10 thoroughly unfamiliar selections from composers remembered as one-trick ponies. Pietro Mascagni is represented not by "Cavalleria Rusticana" but by "Iris" and "Lodeletta"; Alfredo Catalani, by an aria from "La Wally" but not the familiar one. A risqué showstopper from Riccardo Zandonai's "Conchita" wins out over his swooning "Francesca da Rimini." Ruggero Leoncavallo, of "Pagliacci" fame, is heard from in excerpts from his "La Bohème" and from "Zazà."

The scene from "Zazà," running some 10 minutes, is the album's most extended and unusual offering. Zazà, a music-hall performer, calls on her lover only to discover from his little daughter — who does not sing but speaks in a piping voice, and also picks out an "Ave Maria" by Cherubini on the piano — that he is two-timing her as a happily married family man.

Like much else in Ms. Fleming's program, this is classic four-hankie material. Fallen women loom large in verismo, and in the minds of many opera fans their music cries out for sobbing, heart-on-sleeve emotionalism. Instead Ms. Fleming ennobles it with her cool classicism, following models both starry and unsung: among them, Gloria Davy, Claudia Muzio, Renata Scotto and Lynne Strow Piccolo.

Many of the recordings that influenced Ms. Fleming were brought to her attention by her invaluable ally Roger Pines, dramaturge of the Lyric Opera of Chicago. "A while back I read a book called 'The Last Prima Donnas,' by Lanfranco Rasponi," Mr. Pines said recently, "and it got me curious about all sorts of artists and repertoire I hadn't known." How viable the forgotten verismo titles might be in the opera house is an open question. "I do think 'Zazà' and 'Conchita' should be seen," he said. "In other cases the dramatic content may be too purple for audiences today."

Ms. Fleming, for her part, forges on in her quest for new material. "I just work by hook or by crook," she said. "I don't want to record anything unless it can be great and genuinely interesting. When I see 30 recordings of the same title, I think, 'That's not a good idea.' "

Ms. Bartoli conducts her research with a little team of scholars. For "Sacrificium" libraries were combed from Naples to Stockholm, Oxford to Berlin.

"I made my name singing Rossini," Ms. Bartoli, 43, said recently from Vienna, "and I still sing Rossini. He was a great composer, and his music is great for maintaining the flexibility of the voice. But Rossini came from somewhere. Going backward from Rossini I discovered Mozart and Haydn. From Mozart and Haydn, I came to Gluck and Vivaldi and Salieri. One thing leads to another."

Whether showcasing neglected composers, a superstar of yesteryear (Maria Malibran) or a forgotten chapter of music history (the prohibition of opera in Rome at the turn of the 18th century), Ms. Bartoli has never failed to produce a program of striking originality.

In "Sacrificium" — a collaboration with the period orchestra Il Giardino Armonico, conducted by Giovanni Antonini — she investigates the scandalous and macabre phenomenon of the castrati. The earliest documented cases of boys surgically altered to preserve their soprano or alto voices go back to the mid-16th century. The last we know of was Alessandro Moreschi, a singer at the Sistine Chapel, who died in 1922 in his early 60s, leaving behind some ghastly gramophone records cut two decades before.

Moreschi's is the only castrato voice to have been preserved on disc. It cannot bear much resemblance to those of legendary 18th-century superstars like Farinelli, Caffarelli and Senesino, who had the capitals of Europe at their feet. "They were the rock stars of their day," Ms. Bartoli said.

For the cover and booklet of "Sacrificium" grave portraits of the ebullient Ms. Bartoli's face have been grafted onto the nude male bodies of antique statuary, an allusion, she said, to the androgynous appeal of a woman's voice emanating from a male body. Occasional low-lying phrases she takes in a smoky "masculine" chest voice point in the same direction.

"When people think of the castrati, they think of incredible technique," Ms. Bartoli said. "But Nicola Porpora, who taught many of the greatest of them, including Farinelli, and composed for them, always emphasized expression and emotion, the nuance in the words."

In "Sacrificium" Ms. Bartoli runs the gamut from unbridled fireworks (in the forgotten Francesco Araia's "Cadrò, ma qual si mira," described in the notes as "probably the most difficult Baroque aria ever written") to exquisite delicacy (Porpora's "Usignolo sventurato," which mimics the nightingale).

But the scholarship behind some sensational claims made in the extensively annotated booklet that accompanies the CD lacks a certain critical skepticism. For one thing, Ms. Bartoli and her co-author, Markus Wyler, suggest that the papal ban on women singing in public and the craze for castrati resulted in sexual violence against hundreds of thousands of boys in the name of art.

The best support Ms. Bartoli can muster for this statistic is Voltaire's outrageous satire "Candide." ("I was born in Naples," a fictitious eunuch declares, "where they caponized 2,000 to 3,000 boys a year.")

Elsewhere the booklet says that the cry "Evviva il coltellino!" ("Long live the scalpel!") "probably rang out thousands of times in the Baroque opera houses" without a shred of evidence that it rang out anywhere even once.

"I think we found that in Franz Haböck," Ms. Bartoli said, unfazed. (The study in question, published in the 1920s, is hard to lay hands on.) As for the statistic of hundreds of thousands of butchered boys, she did not insist on it but fell back on matters not in dispute: the existence of four Neapolitan conservatories that trained castrati; the outcast status of castrati who did not make it to the top; the unsanitary conditions of the surgical procedures, mostly carried out by barbers, which could lead to infection and death.

Numbers aside, the personalities, alliances, rivalries and social milieu commemorated on the CD are vibrantly alive in Ms. Bartoli's imagination, and she bring them to life in the music.

"If I sang nothing but Rossini all my life, I'd be in one space," she said. "To make your own space, you have to do research. You have to go deep. My space keeps changing."