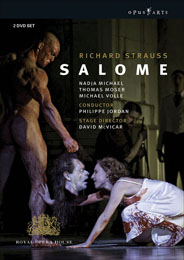

A concept, a conception — what's the difference? David McVicar's Salome for Covent Garden, new last season, answers that question with the force of revelation.

The imagery, as disclosed in the expendable making-of documentary "David McVicar: A Work in Process," derives from Pasolini's stomach-turning, widely banned Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom. Hence the fashions of the 1930s, the slaughterhouse-meets-bordello ambience (designs by Es Devlin). Yet far from using these references to footnote some contrived thesis, McVicar delves straight into the hearts and minds of his characters, with compassion where compassion is in order, but unmoved by mawkish sentiment. The Dance of the Seven Veils (choreographed by Andrew George) is not the striptease of cliché but imagist dance theater of a high order. The real world disappears as the waiflike Salome and a mammoth Herodes in formal wear traverse seven rooms, reliving cryptic scenes of pedophilia. Some byplay with a rag doll, with a mirror and a scarf, some waltzing, a stolen embrace, some undressing but no nudity, some splashing in a sink of water — these are stations of a degradation that leaves her strangely untouched. Amid the corruption, she clings to some private ideal of innocence. Salome's preoccupation with chastity (the moon's, Jochanaan's) is rarely so clear or so consequential as in this staging.

The imagery, as disclosed in the expendable making-of documentary "David McVicar: A Work in Process," derives from Pasolini's stomach-turning, widely banned Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom. Hence the fashions of the 1930s, the slaughterhouse-meets-bordello ambience (designs by Es Devlin). Yet far from using these references to footnote some contrived thesis, McVicar delves straight into the hearts and minds of his characters, with compassion where compassion is in order, but unmoved by mawkish sentiment. The Dance of the Seven Veils (choreographed by Andrew George) is not the striptease of cliché but imagist dance theater of a high order. The real world disappears as the waiflike Salome and a mammoth Herodes in formal wear traverse seven rooms, reliving cryptic scenes of pedophilia. Some byplay with a rag doll, with a mirror and a scarf, some waltzing, a stolen embrace, some undressing but no nudity, some splashing in a sink of water — these are stations of a degradation that leaves her strangely untouched. Amid the corruption, she clings to some private ideal of innocence. Salome's preoccupation with chastity (the moon's, Jochanaan's) is rarely so clear or so consequential as in this staging.

The set is on two levels — an upper dining room high in the frame of the proscenium and the tiled utility area below, connected by a monumental curving stairway. The documentary shows McVicar staging the banquet upstairs in elaborate detail, but the cameras in the auditorium capture none of that: they have too much else to focus on. The former mezzo-soprano Nadja Michael makes a mesmerizing Salome, demure in white satin, watchful as a snow leopard. Her eyes gaze out as from the mask of a china doll, missing nothing, giving nothing away. Michael Volle presents Jochanaan as a raging beast, so thoroughly in the grip of his demons as scarcely to notice Salome until she has crept much too close. Thomas Moser's Herodes is an ogre past caring what the world thinks of his transgressions, shadowed by a bovine Herodias (Michaela Schuster) who cannot manage him.

From the pit, Philippe Jordan conjures up fleeting tone poems of startling specificity — a ballroom here, a barracks there — all aglow with the requisite moonbeams and torchlight. The vocalism in general is highly satisfactory, though Michael's Salome is reaching for the moon, at her peril. Counterintuitively, the strain on her light instrument shows most in soft passages late in the opera, in notes that are perfectly steady, seamlessly integrated into the phrase and sorely off pitch. Pity the listener for whom these flaws break the spell.

For the record, McVicar's Herculean executioner was discovered outdoors at Covent Garden, working for coins as a living statue. On the stage of the Royal Opera House, he emerges from the cistern buck naked, drizzled with stage blood from top to toe, bearing a severed head that sets a standard for naturalism unlikely to be surpassed. Salome ends up bathed in gore, basking in sheer rapture. At Herodes's command, the executioner snaps her neck and lays her down as if to sleep — the loving protector she never had.

Michael, Schuster; Volle, Moser, Kaiser; Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, Jordan. Production: McVicar. Opus Arte OA 0996 D, 169 mins., subtitled.