Here's the rundown on our playlist of July 29. Beneath the section break, look for commentary on our selections for August 5.

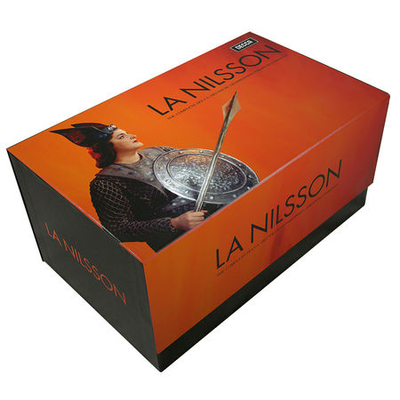

In happy receipt of the limited-edition centennial treasure chest La Nilsson (Decca), we could, I thought, offer the diva no less than a miniature retrospective of our own. A farmer's daughter from Sweden, Birgit was a powerhouse of the first magnitude. To say that she stood alone in her generation would cast unconscionable shade on an honor roll of incandescent colleagues—Astrid Varnay, Martha Mödl, Leonie Rysanek, for starters, and these were hardly the only ones. Yet in the punishing German heavyweight repertoire these ladies shared, for many, Nilsson reigned supreme. As Puccini's bloodthirsty princess Turandot, carving her phrases in liquid nitrogen, she had no competition at all. Has this planet ever heard the like?

In happy receipt of the limited-edition centennial treasure chest La Nilsson (Decca), we could, I thought, offer the diva no less than a miniature retrospective of our own. A farmer's daughter from Sweden, Birgit was a powerhouse of the first magnitude. To say that she stood alone in her generation would cast unconscionable shade on an honor roll of incandescent colleagues—Astrid Varnay, Martha Mödl, Leonie Rysanek, for starters, and these were hardly the only ones. Yet in the punishing German heavyweight repertoire these ladies shared, for many, Nilsson reigned supreme. As Puccini's bloodthirsty princess Turandot, carving her phrases in liquid nitrogen, she had no competition at all. Has this planet ever heard the like?

Our three-part tribute—the tip of an 80-disc iceberg—opened with Scene 3 from Act 1 of Wagner's Tristan und Isolde, including the narrative-and-curse sequence: a cyclone of rage and spite, punctuated by aching lulls of tenderness, shame, and woe, all urging the heroine on to murder-suicide.

The poisoned chalice, or is it? Nilsson as Isolde. |

Critics who were born yesterday like to scoff that divas of past generations—unlike today's camera-ready models—used to "stand and deliver." In a sense that is true, of those who had vocal goods we have not heard the likes of in many a year. But the implication that such artists lacked either drama or nuance is pure slander. Few voices have ever conveyed more slashing, metallic power than Nilsson's. Yet notes of vulnerability and tenderness were at her command as well, and in this great encounter, we hear them.

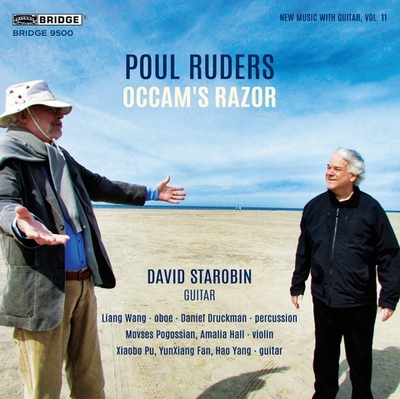

Next up: miniatures from the guitarist David Starobin's new album Occam's Razor (Bridge), devoted to the Danish composer Poul Ruders. We heard the opening and closing movements of the title suite, with Liang Wang seconding on oboe. Also known as the law of parsimony, Occam's razor is the philosophical principle that the best solution to a problem is the one that rests on the fewest assumptions. That would seem to chime with the extreme concision of these very deft, elegant, but also curiously elusive statements.

Next up: miniatures from the guitarist David Starobin's new album Occam's Razor (Bridge), devoted to the Danish composer Poul Ruders. We heard the opening and closing movements of the title suite, with Liang Wang seconding on oboe. Also known as the law of parsimony, Occam's razor is the philosophical principle that the best solution to a problem is the one that rests on the fewest assumptions. That would seem to chime with the extreme concision of these very deft, elegant, but also curiously elusive statements.

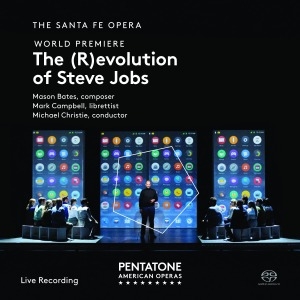

Almost exactly a year after the world premiere at the Santa Fe Opera, The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs is available for home listening (Pentatone). The early tableau "Product Launch," wherein the Man Who Was Apple introduces the iPhone, makes a knockout case not only for the propulsive score by Mason Bates but also for Mark Campbell's sharp text. Not since the buoyant "News!" monologue of Nixon in China (libretto by Alice Goodman, music by John Adams) have I come across a set-up that packs such a jolt. Edward Parks is on his toes as Steve, with Santa Fe's chorus and orchestra in crisp counterpoint. Michael Christie is the conductor.

Almost exactly a year after the world premiere at the Santa Fe Opera, The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs is available for home listening (Pentatone). The early tableau "Product Launch," wherein the Man Who Was Apple introduces the iPhone, makes a knockout case not only for the propulsive score by Mason Bates but also for Mark Campbell's sharp text. Not since the buoyant "News!" monologue of Nixon in China (libretto by Alice Goodman, music by John Adams) have I come across a set-up that packs such a jolt. Edward Parks is on his toes as Steve, with Santa Fe's chorus and orchestra in crisp counterpoint. Michael Christie is the conductor.

And to close, we had the "Songs About the Sea" from Gisle Kverndokk: Symphonic Dances (SSO), brought to us by Norway's Stavander Symphony Orchestra, led by Ken-David Masur, late-blooming scion of the illustrious Kurt Masur, long-time leader and conscience of Leipzig's Gewandhaus Orchestra. Melodious, episodic, painted in alluring instrumental colors, the ten-minute voyage navigates waters that run deep beneath a serene surface.

And to close, we had the "Songs About the Sea" from Gisle Kverndokk: Symphonic Dances (SSO), brought to us by Norway's Stavander Symphony Orchestra, led by Ken-David Masur, late-blooming scion of the illustrious Kurt Masur, long-time leader and conscience of Leipzig's Gewandhaus Orchestra. Melodious, episodic, painted in alluring instrumental colors, the ten-minute voyage navigates waters that run deep beneath a serene surface.

*

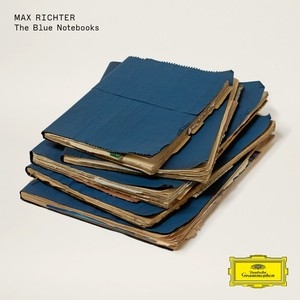

On August 5, we opened with the Deutsche Grammophon reissue of The Blue Notebooks, an early double album from Max Richter. Obscure to the point of invisibility 15 years ago, the German-born British composer and all-around keyboardist has emerged as quite the cult icon. (My indoctrination came with the eight-hour-plus Sleep, which has been performed live as an all-nighter in ad hoc dormitories, complete with beds, pillows, and covers. You can also partake at home, in a bed of your own. Highly recommended. Digital downloads available.) Some have called Richter a minimalist, some a postminimalist, which may be labels as descriptive as any. From my limited exposure, I prefer to think of him as perhaps the Vivaldi of the Alpha State: dreamy, vague, celestially restful. We heard the opening track ("The Blue Notebooks"), with voiceover by the Circean Tilda Swinton, and a bonus track called "Cypher," about which I cannot think of a single thing to say. But please don't construe that as a put-down.

On August 5, we opened with the Deutsche Grammophon reissue of The Blue Notebooks, an early double album from Max Richter. Obscure to the point of invisibility 15 years ago, the German-born British composer and all-around keyboardist has emerged as quite the cult icon. (My indoctrination came with the eight-hour-plus Sleep, which has been performed live as an all-nighter in ad hoc dormitories, complete with beds, pillows, and covers. You can also partake at home, in a bed of your own. Highly recommended. Digital downloads available.) Some have called Richter a minimalist, some a postminimalist, which may be labels as descriptive as any. From my limited exposure, I prefer to think of him as perhaps the Vivaldi of the Alpha State: dreamy, vague, celestially restful. We heard the opening track ("The Blue Notebooks"), with voiceover by the Circean Tilda Swinton, and a bonus track called "Cypher," about which I cannot think of a single thing to say. But please don't construe that as a put-down.

To pick up the pace, we dropped the laser on Myroslav Skoryk's "Three Extravagant Dances for Piano Four Hands," from the album Ukrainian Rhapsody (Sorel Classics), a tribute to composers of their troubled homeland by Anna & Dmitri Shelest, a couple now residing in New York. The tracks are "Entrance and Dance: Almost Spanish-Moorish," "Blues: Almost American," and "Can-Can: As From an Old Gramophone Plate." Skoryk's stylish, flashy writing makes good on the promise of each of the pastiche titles, and the pianism verges on the symphonic, with colors by Technicolor.

To pick up the pace, we dropped the laser on Myroslav Skoryk's "Three Extravagant Dances for Piano Four Hands," from the album Ukrainian Rhapsody (Sorel Classics), a tribute to composers of their troubled homeland by Anna & Dmitri Shelest, a couple now residing in New York. The tracks are "Entrance and Dance: Almost Spanish-Moorish," "Blues: Almost American," and "Can-Can: As From an Old Gramophone Plate." Skoryk's stylish, flashy writing makes good on the promise of each of the pastiche titles, and the pianism verges on the symphonic, with colors by Technicolor.

A lady to reckon with: Nilsson takes charge in Macbeth, Stockholm, 1947. |

From the complete recording, conducted by Thomas Schippers in Rome in 1964, we listened in on Lady Macbeth's three most private and revealing moments: in the Letter Scene, bracing to spur Macbeth to murder; in first gloomy, then manic contemplation of the necessity of further bloodshed ("La luce langue"); and finally, in the Sleepwalking Scene, cocooned in candlelight and Gothic shadows. At the outset, Nilsson's icy soprano slashes like the steel of an exterminating angel yet pierces like a spear. As Lady's deeds (yes, in deference to Verdi, we melomanicall her "Lady") come back to haunt her, the Satanic grandeur disintegrates, yet without sacrifice of the core quality of Nilsson's sound. The imaginative accomplishment and the integrity of vocal technique go hand in hand. More to the point, they are one.