Above the war zone that is opera hang the memories, like mournful ghosts, of countless young talents that flared early and burned out before their time, done in, we like to think, by impresarios who offer too much too soon. But true greatness makes its way. "Lead me not into temptation" is no prayer for a hero.

Above the war zone that is opera hang the memories, like mournful ghosts, of countless young talents that flared early and burned out before their time, done in, we like to think, by impresarios who offer too much too soon. But true greatness makes its way. "Lead me not into temptation" is no prayer for a hero.

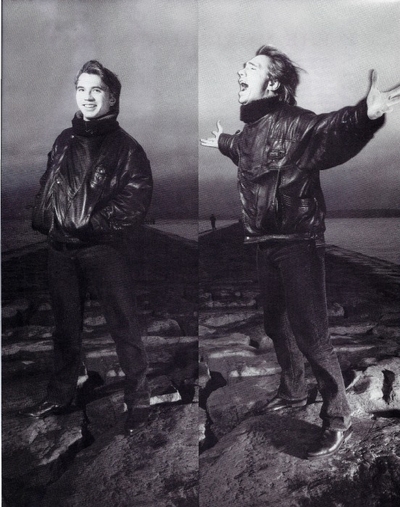

No one in opera is more beset by tempters just now than the twenty-seven-year-old Siberian baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky. His potential is boundless. The voice is somber yet sumptuous, like the hues of Rembrandt, noble, red-blooded, as fit for tenderness as for command. The presence is commanding, too. Broad-shouldered, of imposing height, he takes the stage with a conqueror's stately pride. In repose, his countenance impresses with its swelling cheekbones, sensuous mouth, dark hair shot through with metallic early gray, and almond eyes that unlock souls as they slowly sweep the hall. When he sings, he is more beautiful still, knitting his brows and baring his teeth like a tiger, letting those eyes droop shut in private rapture. Caravaggio would have loved to paint him. "Don't I look like a rock star?" he asked London's entertainment magazine 20/20 not long ago. Maybe, or maybe some seducer-by-trade of another tribe: an evangelist.

But no flimflam taints the spell he casts. Consider his reading of Tchaikovsky's meditation "Podveeg" (Exploit):

There is glory in battle,

There is valor in struggle,

But the highest honor is in patience,

Love, and devotion.

With this brooding stanza the song begins; to this stanza it at last returns. With a show of cheap piety, you could sell it. Hvorostovsky "shows" nothing, sells nothing. Lost in its solemnity, grave and alone, he floods one's being in the sound of his voice. In "Don Juan's Serenade," where Tchaikovsky strikes a swashbuckling, Slavic-stage-Spanish vein, Hvorostovsky is perfect again: predatory, orchidaceous, demonic. Without acting, merely through poetic concentration, he sculpts a song through the moment the piano's last note dies, but then breaks forth, if he is content with himself and the audience, in a blazing grin. It sounds as if something would have to ring false, but, strangely, nothing does.

Hvorostovsky's gifts transcend his medium. Unlike Placido Domingo, say, who has vainly courted the masses with nightclub tunes and zarzuela shows, Hvorostovsky has it in him to enchant people with no prior interest in opera or classic song. He belongs in the charmed circle of Enrico Caruso, John McCormack, Marian Anderson, Paul Robeson, Fyodor Chaliapin, and Ezio Pinza, in the past, or Luciano Pavarotti, Jessye Norman, and Kathleen Battle, today: stars on whom fame descend—popular fame, fame on the grandest scale—without exacting from them any betrayal of their native genius.

The West first took notice of him exactly a year ago, on the occasion of the BBC's Cardiff Singer of the World competition. Strictly for the trade, one might suppose, but not this time. Hvorostovsky (Westerners who choke on the initial Cyrillic x—variously transliterated as h, ch, or kh and pronounced like the ch in the Scots word loch—may drop it and say vah-rah-STOV-sky, which is close) presented himself with "Ombra mai fu," from Handel's Serse, known to churchgoers as "Handel's Largo"; songs by Hugo Wolf, Rachmaninoff, and Tchaikovsky; a favorite aria from Tchaikovsky's The Queen of Spades; and three scenes from Verdi, capping the finals with the death of Rodrigo from Don Carlo, unfolded in phrases so endless and so smooth they left listeners breathless with wonder.

Live telecasts carried the proceedings into millions of British households, and as the offers began pouring in from La Scala, Covent Garden, the Berlin Opera, not to mention record companies and the world's top orchestras, ordinary people started accosting him on the street to tell him how wonderful they thought he was. Everyone wanted more. But what else was there?

Other than what Hvorostovsky had shown in Cardiff, the kingmakers knew nothing about him. Where did he come from? What did he know?

Here are some answers. Dmitri Hvorostovsky was born on October 16, 1962, in the Siberian city of Krasnoyarsk, exactly halfway around the globe from Peoria, and its cultural reputation among cosmopolitan Soviet citizens is about what Peoria's is here. Somewhat unfairly, as it happens, since its population of under one million supports, by Hvorostovsky's count, two opera houses, two playhouses, a children's theater, and a symphony orchestra with its own, splendid hall, in addition to other venues for chamber and organ recitals, along with a music school and a conservatory.

The only child of a chemical engineer and a doctor, both good amateur musicians, Hvorostovsky was sent at an early age to music school, where he studied piano and conducting and sang in the chorus. At twenty, he began to work at the local conservator—initially as a tenor—with the voice teacher Jekatherina Konstantinova Yofel, otherwise unknown to us. She is "like a hypnotist, " according to her star pupil. "With her, even exercises have feeling." Like playing Bach? "Yes! Like Glenn Gould playing Bach!"

After four years with Yofel—this takes us to 1986--Hvorostovsky joined the Krasnoyarsk Opera, "a big opera house," as he describes it, "with bad acoustics." After unnoticeable walk-ons in Rigoletto, La Traviata, and Tosca, he graduated to better assignments, like Silvio, in Pagliacci; Valentin, in Faust; Germont, in La Traviata; and Tchaikovsky's Prince Yeletsky, in The Queen of Spades, Robert, in Iolantha, and Eugene Onegin (to date his only bona fide lead). In 1987, he took first prize at a singing competition in Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan, where he attracted the notice of the legendary Soviet mezzo-soprano Irina Arkhipova; in 1988, he took another first in the French town of Toulouse, which led to an engagement to sing The Queen of Spades in Nice the following fall.

Before Cardiff, he had been to America, too. In April 1989, when the San Francisco grass-roots organization Beyond War invited Arkhipova to take part in some Soviet-American concerts to promote cultural understanding, she brought him along with a clutch of rising singers she hoped to commend to attention of Western managers. The concerts for peace drew good crowds, but no auditions materialized. Undaunted, Arkhipova arranged some ineptly promoted recitals. In Los Angeles, Martin Bernheimer, the music critic of the Los Angeles Times, estimated attendance at no more than 200, in a hall seating 1,270—"embarrassing," he called it. But he was impressed by the talent, singling Hvorostovsky out as "the greatest revelation." "If he always sings as he did on this occasion, " Bernheimer wrote, "he could have the world at his feet."

But not right away. Days later, the Arkhipova traveling show played Symphony Space, an unfashionable venue on Manhattan's Upper West Side. Of the people who count in the American music world, only two bothered to check in. Eve Queler, the music director of Opera Orchestra of New York, which presents opera in concert at Carnegie Hall, was scouting for affordable talent; she offered Hvorostovsky a contract as a cover for the scheduled baritone in Tchaikovsky's The Maid of Orleans the following February. Will Crutchfield, from the New York Times, was on hand, too, and gave the singer's unaccompanied rendition of the folk song "Nochenka" (Night) a rare unqualified "marvelous." Other than that, he worried about "the pressure [Hvorostovsky] puts on his loud notes, which turned stiff and sometimes hoarse." The soprano Natalya Datsko, he felt, the Arkhipova protégé to watch.

As things turned out, Hvorostovsky did not cover The Maid of Orleans, and Queler presented him at Alice Tully Hall in his New York debut recital, with piano, the following Sunday. Never before had she put on a concert without personally climbing the podium and waving her stick. Though not a single advertisement had appeared in any newspaper, the tickets had vanished from the box office instantly. The previous December, Hvorostovsky had confirmed his Cardiff conquest with two sold-out recitals in London. Now, in New York, the music world's highest and mightiest were ranged like powers of the Inquisition.

Hvotostovsky's program—nine songs of Tchaikovsky followed by nine songs of Rachmaninoff—contained no conventional crowd-pleasers. But the encores brought his prizewinning Verdi, and the house came down. Then Hvorostovsky returned alone, sat down at the keyboard, struck a chord, rose again to a baffled laugh from the audience, and announced, "Last my song. 'Nochenka'—'Night.'" No one was prepared for what followed: a serpentine lament whose swelling and fading arabesques reached back to the dawn of time. Marvelous indeed.

What on earth is it all about? Hvorostovsky does not trust explanations. "Like a lot of Russian songs," he offers in English that improves each day, "it has two meanings, maybe more. To understand a Russian song, you must be a Russian person."

Are the words a secret?

Hvorostovsky drags deeply on his American cigarette. Despite that mesmerizing gaze in the hall, beyond a few feet he sees nothing clearly without the thick glasses he wears offstage. He seems to like it that way. "I feel the connection with the audience," he has told me. "Sometimes." Now, in the privacy of his room, he closes his eyes.

Dark night, autumn night,

I have no mother, no father,

Only my beloved,

Who lives with me

And does not love me.

That's all? "That's all!" Hvorostovsky bursts into laughter. "Russian people are somewhat strange. We ask why. Why do I live? Nobody knows why. Russian literature, Russian music is full of this question. Moussorgsky, Tolstoy, Tchaikovsky .... " Is self-mockery creeping in? "Pain and happiness," and he continues in portly tones, "light and night. In this question, there are deep philosophical thoughts. That's my joke. I'm sorry ... "

How can this talent be harnessed? It is too grand, too untamed for the workaday opera world to contain. Consequently, Hvorostovsky's experience still lags far behind his manifest ability. Blame his voice category. As the history of opera is written, especially in the Italian repertory for which Hvorostovsky's glamorous tones and phrasing are made to order, the baritone is the tenor's confidant or father, the prima donna's rejected suitor or betrayed husband—no roles for a charismatic youngster. One admirer of Hvorostovsky's fantasizes about a new opera of Dracula just for him; another dreams dreams of a Liaisons Dangereuses. But who will write them?

In the realm of actualities, everyone in the business can see him as Onegin, which he will sing at La Fenice, in Venice, in early 1991, in his first major appearance in the West since Cardiff; or as Verdi's Rodrigo, in Don Carlo, the vehicle for his debut at La Scala on the opening night of the 1991 season. Five or ten years down the road, heavier parts like Verdi's Count di Luna (in Il Trovatore), Renato (in Un Ballo in Maschera), Iago in Otello), and Rigoletto should be his own. For now, carving out a niche will require a certain art.

Corning off his triumph at Cardiff, Hvorostovsy could have shaken hands with many devils. There was the Bolshoi Opera, dangling a contract giving him his pick of roles and the pampered life of a favore Soviet artists. "I didn't see my future there," Hvorostovsky says. Moscow, even post-glasnost, would be a gilded cage. "The artists are not free. They get offers from the West and are not allowed to accept them. I have to work in the best houses, with the best conductors. That's very important. But the most important thing is to work as a free man."

Freedom has its pitfalls. Hvorostovsky could also have gone hustling the international opera circuit. Instant possibilities were not lacking, but these did not suit him either. Except for Onegin, the roles he knew no longer seemed worth his time. Roles he wants but does not yet know were offered, too: Rossini's Figaro in The Barber oj Seville, for instance, and Verdi's Rodrigo, whose death scene he enacts in concert so unforgettably. Leonard Bernstein, for whom Hvorostovsky auditioned privately in London, embraced him and gushed, "You are Don Giovanni," no doubt forgetting for the moment that Mozart's rake has not a single great number to sing in a score that is otherwise all marvels. Hvorostovsky had heard the line before, from girls at the stage door. He looks the part, but what is in it for him? A Salzburg festival debut in a new production in 1993, if he wants it. His own wish list runs to bel canto rarities: Donizetti's La Favorita, which he will sing in Brussels in November 1991; Bellini's I Puritani, in his datebook for 1992 at Covent Garden.

The greatest challenge now is to take his time. "My life has taken a hard turn," he remarks. "When I learn a song or a new role, I listen to many recordings and watch many tapes. I have a lot of literature and really good friends who help. And I go to the library. That's the ideal. But now I'm not at home. I study in hotels, airplanes, the metro. It's terrible! I have to work alone."

So the concert stage is his salvation. Only there can he control his pace, maintain the presence he wants both in the Soviet Union and in the West, and keep the spotlight, too. Except for starring roles under festival conditions—when the colleagues and venues are right and the productions are new—opera ties up too much time to justify the narrow exposure.

An impatient world must settle for tantalizing glimpses. London, New York, and Washington have heard Hvorostovsky only in his Tchaikovsky-Rachmaninoff programs, with Verdi relegated to the encores. His interest in bel canto is now a matter of public record, but no one outside Dublin really has any inkling just how splendidly it suits him. Dublin? After a hospital stay the Cork impresario Barra Ó Tuama (nicknamed Boris Ó Tuamovich, for his predilection for Soviet singers) caught Hvorostovsky on television during the semifinals in Cardiff and offered him a tour of Ireland in February, "win, lose, or draw."

Hvorostovsky accepted and was programmed on a shared bill of opera arias with an Irish soprano and a Welsh tenor, accompanied on the piano. After turning away thousands in Cork and in Dublin, Ó Tuama quickly arranged a solo recital in Dublin for Hvorostovsky two nights after his first outing there. The vaguely Victorian salon setting that is Ó Tuarna's hallmark—a master of ceremonies presiding over a stage decked out with sofa, lamps, and flowers—complemented Hvorostovsky's nostalgic program exquisitely; it was a scene from James Joyce, filled with song that tugged the heartstrings and at the same time stopped one's breath with sheer joy. Giordani's lover's plea "Caro mio ben," which Pinza used to sing (ravishingly) as a silken caress, broke forth in a piercing cry. The slow sections of Donizetti arias charmed the ear with warm, flowing elegance; the allegro sections, with rippling scales and rhythmic snap. The world's music capitals have a treat in store.

Three nights later, at a fund-raiser for the National Art Collections Scottish Fund at Usher Hall, in Edinburgh, Hvorostovsky sang, with the Scottish Opera Orchestra, a program of Slavic and Italian opera arias. Along with some swift Dutch managers, who brought Hvorostovsky to Holland last fall, and like Ó Tuama in Ireland, the Scots had signed Hvorostovsky early. Edinburgh was the watershed: Dmitri's last gig in the sticks. Henceforward, it would be nothing but the big time.

He might have coasted, but no. Along with his most polished Tchaikovsky and Verdi, he brought something new: his first performance with orchestra of the popular Prologue from Leoncavallo's Pagliacci. In the theater, the singer would begin in midoverture, popping his head through the curtain and interrupting with a prefatory message from the author. On the concert platform Hvorostovsky had to stage it his own way if at all. So, on cue, he popped out from the swinging door at stage right, put his throat-clearing excuses to members of the orchestra as he passed, hit his mark front and center right on time for the big announcement "Io sono il prologo!," and with an expansive gesture took in the whole hall.

It was an instinctual masterstroke, and there was more. The Prologue's point is to stress the truth of the action that is to follow, to urge the bond of common humanity between the spectators and the players. One lovely passage evokes the "nest of memories" that was the author's inspiration, and its high, soft setting seems calculated for crooning, for easy nostalgia. Floating the lines as handsomely as one could wish, Hvorostovsky tinged them with a mysterious bitterness, disturbing, original, and true.

Where, one wonders, not really expecting an answer, does he find such things? "I listen and I learn," the singer replies. "It's not possible to express in words. These are feelings of the heart and mind. I don't study a manner. To study that way is impossible. In a sense it is forbidden."

"What I want," he continues, "is for the audience to understand the feelings. Even if there are technical flaws, I have to sing with feeling as if it were the first time. If I stop giving that, I must stop my career."

This is just the beginning.