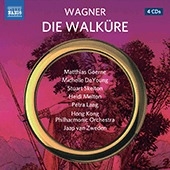

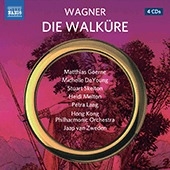

Started out with a big haul today: Die Walküre, the second installment in Richard Wagner's four-part, 17-hour epic Der Ring des Nibelungen, with Jaap van Zweden leading the Hong Kong Philharmonic and an international cast of important soloists (Naxos, four CD's). From the realms of fable of the curtain-raiser Das Rheingold, which is peopled by gods, dwarves, and giants, we now descend to earth. The great tug-of-war between power in the sense of coercion and the higher power of love continues, with colorful new players on the field. Act 1 introduces the heroic Siegmund, dogged by misfortune, and his long-lost twin sister Sieglinde, miserable in a forced marriage to the brutal warrior Hunding.

Started out with a big haul today: Die Walküre, the second installment in Richard Wagner's four-part, 17-hour epic Der Ring des Nibelungen, with Jaap van Zweden leading the Hong Kong Philharmonic and an international cast of important soloists (Naxos, four CD's). From the realms of fable of the curtain-raiser Das Rheingold, which is peopled by gods, dwarves, and giants, we now descend to earth. The great tug-of-war between power in the sense of coercion and the higher power of love continues, with colorful new players on the field. Act 1 introduces the heroic Siegmund, dogged by misfortune, and his long-lost twin sister Sieglinde, miserable in a forced marriage to the brutal warrior Hunding.

From Siegmund's narrative of his tragic backstory, we heard an excerpt consisting of the consecutive tracks "Friedmund darf ich nicht heissen" and "Die so leidig Los dir beschied," delivered by the Australian heldentenor Stuart Skelton in firm, clear, and arresting tones—but minus the pathos that wrings the heart in his previous live recording of this music from the Seattle Opera. The likely culprit here has to be Van Zweden, leading this mammoth score for the first time with an orchestra likewise new to the assignment. Apparently preoccupied by technical demands, they soldier on at plodding tempi, hardly beginning to probe beneath the surface. In brief interjections, the German bass-baritone Falk Struckmann nevertheless brings Hunding icily to life, while the American soprano Heidi Melton, pours on the kind of thrilling, lavish tone Deborah Voigt commanded at the rise of her stellar career. (But her German needs work.)

In Wotan's wheelhouse? Matthias Goerne does it his way. |

With Act 2, the gods return. The German baritone Matthias Goerne portrays Wotan, their autocratic chief, forced here to face the consequences of prior misdeeds. Probably best known as a concert singer, Goerne towers among the heirs of the late Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, who stood alone. He is likewise a remarkable stage animal, unforgettable in roles from the sunny bird-catcher Papageno in Mozart's

Magic Flute to the homicidal, likely schizophrenic soldier Wozzeck in Berg's expressionist classic of that name. As far as repertoire goes, he writes his own rules, often to the consternation of critics and colleagues, seldom without striking results.

The intellectual, emotional, and spiritual journey falls well within Goerne's wheelhouse, but how about the heavyweight vocal demands?

In the final paragraph of Wotan's great Act 2 monologue (from "So nimm meinen Segen, Niblungensohn), Goerne invests less self-contempt and authoritarian fury than his most memorable predecessors. To say that the low-lying phrases come easy would not be true, but the difficulty injects an appropriate visceral note Goerne seems otherwise at pains to avoid. As so often, he is remaking his material in his own image. In Van Zweden, who seems to be coming to the project unencumbered by traditional baggage, Goerne may have the ideal collaborator. Certainly further exploration is in order. To round out our quick survey, we cut to the Technicolor "Ride of the Valkyries"—not, of course, the familiar, purely instrumental concert version, but the real thing, with an electrifying complement of seven warrior maidens to blow off the roof. All concerned rose spectacularly to the occasion.

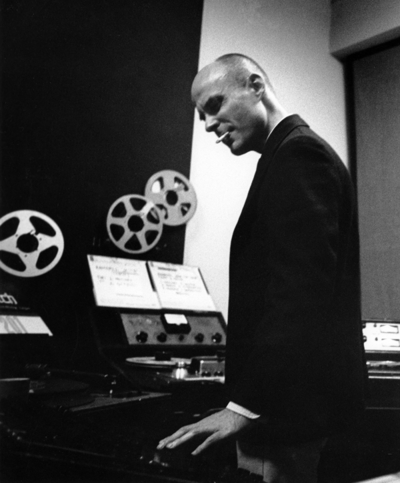

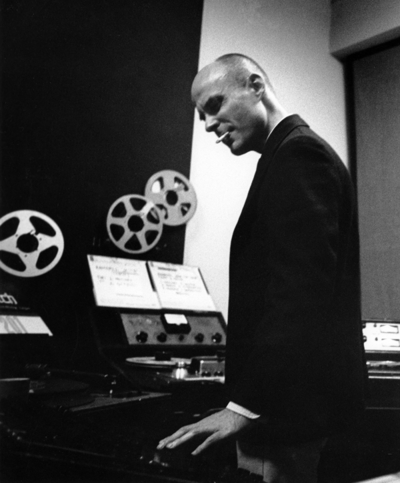

Tod Dockstader: a man in his element. |

From here, we took a quantum leap to the electroacoustic experiments of the late

Tod Dockstader (1932-2015), whose following, such as it was, consisted largely of fellow underground composers. By day, Dockstader began his career editing film and creating sound effects in Hollywood, then moved on to New York as a sound engineer. A quartet of LP's in the mid 1960s put him on avant-gardists' radar. Despite the excitement, he released nothing more for three decades, and thereafter only sporadically. After his death, his daughter discovered some 4,200 sound files produced between 2000 and 2008. This legacy is the source of the lovingly selected 15 tracks that make up

Tod Dockstader: From the Archive (Starkland): the tip of the tip of an iceberg. At random, we fished out the eerie, tense "Anat Loop," a collage of banging doors, static, frenetic ratchet sounds, and a dusting of fairy chimes; "Odd Bells," a soundscape that teeters somehow between claustrophobia and agoraphobia; and finally "Whisper Smoothed," a weave of long-sustained breaths and rumblings, punctuated by what might be signals from a distant galaxy. Easy listening? No, yet this is not "difficult" music, either. If its hyperspaces defy analysis, they seldom disorient. And as I've since discovered, Dockstader's sensibility is by no means uniformly nervous-making. Tracks we didn't get to touch many other chords, by turns nimble, playful, and airy.

Usual suspects not invited: the Hungarian-born guitar whiz Zsófia Boros. |

In overtime, we dropped in on

Zsófia Boros: Local Objects, a classical-guitar program from which all the usual suspects have been rigorously excluded (ECM New Series). Of eight composers in the lineup, my co-host Paul Janes-Brown recognized only the jazz legend Al Di Meola—one more than I did. The name that caught my eye, simply because it was the most exotic, was

Franghiz Ali-Zadeh, attached to the single longest track on the album, "Fantasie" by name, nearly nine minutes. Franghis who? Within seconds, Paul was rattling off Ali-Zadeh's bio from Wikipedia, citing Azerbaijani origins, current residence in Germany, and a long association with such starry world-music travelers as Yo-Yo Ma and the quartet known as Kronos. Her guitar fantasy draws kaleidoscopically on Spanish and Moorish traditions that have intermingled for centuries. The demands on the soloist are formidable, but

Boros takes them in stride, drumming stealthily on the wooden body of the guitar here, unfurling bolts of pointillist polyphony there, at times even exploding into the clangor of a gamelan in all its Javanese, metallic splendor.

Started out with a big haul today: Die Walküre, the second installment in Richard Wagner's four-part, 17-hour epic Der Ring des Nibelungen, with Jaap van Zweden leading the Hong Kong Philharmonic and an international cast of important soloists (Naxos, four CD's). From the realms of fable of the curtain-raiser Das Rheingold, which is peopled by gods, dwarves, and giants, we now descend to earth. The great tug-of-war between power in the sense of coercion and the higher power of love continues, with colorful new players on the field. Act 1 introduces the heroic Siegmund, dogged by misfortune, and his long-lost twin sister Sieglinde, miserable in a forced marriage to the brutal warrior Hunding.

Started out with a big haul today: Die Walküre, the second installment in Richard Wagner's four-part, 17-hour epic Der Ring des Nibelungen, with Jaap van Zweden leading the Hong Kong Philharmonic and an international cast of important soloists (Naxos, four CD's). From the realms of fable of the curtain-raiser Das Rheingold, which is peopled by gods, dwarves, and giants, we now descend to earth. The great tug-of-war between power in the sense of coercion and the higher power of love continues, with colorful new players on the field. Act 1 introduces the heroic Siegmund, dogged by misfortune, and his long-lost twin sister Sieglinde, miserable in a forced marriage to the brutal warrior Hunding.