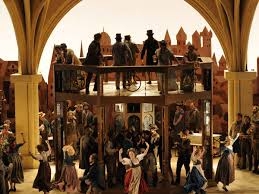

Great expectations: a glimpse of McVicar's Meistersinger, originally mounted in Glyndebourne. |

In a company debut, Sir Mark Elder kept the orchestra on radiant form, unfolding the bejeweled score in spacious, occasionally leaden or metronomic, paragraphs. The singularly festive overture raised the highest expectations, but the brawl at the close of Act 2 fizzled. That's a big fizzle; I'm told that until 1933 the Encyclopaedia Brittanica singled out that stupendous double fugue as the pinnacle of human civiization.

In the main, the cast did itself proud, notably the large continent of artists in important debuts. One of two principals new to the company, the lean Estonian basso Ain Anger looked every inch the part of Pogner, Eva's prosperous, status-conscious father, but his music calls for an expansive nobility Anger's gritty sound does not convey. As Beckmesser, Stolzing's grotesque rival for Eva's hand, the German baritone Martin Gantner downplayed the customary snarling and whining, falling between the stools of objectionable stereotype and a plausible flesh-and-blood alternative, which in truth the role does not support.

Four other principals, all Americans, shone to varying degrees in new roles. As the aristocrat Walther von Stolzing, who in the opera's bourgeois setting is the outsider, the heldentenor Brandon Jovanovich cut the figure of a loose-limbed storybook prince and lent his love songs both power and a golden glow. As Eva, the goldsmith's daughter, the soprano Rachel Willis-Sørensen walked a fine line between ingénue and minx, unfazed by awkward low-lying passages and thrilling in the heights. The diminutive mezzo soprano Sasha Cooke lent Eva's maid Magdalene the incongruous yet delightful edge and profile of a prima donna. (No one else's words or music registered as clearly.) Alek Shrader sang and acted and occasionally danced the role of David, the shoemaker's apprentice, with a music-hall verve and charm you hope for in Oliver!

But in the end, Die Meistersinger stands or falls by its cobbler/philosopher king Hans Sachs, here the English baritone James Rutherford, no novice to San Francisco or the role, which according to his bio he has sung at the Vienna State Opera, Glyndebourne, and the Bayreuth Festival, which was founded by Wagner himself. What can I say? The role is hard to cast.

As chance would have it, I first heard Rutherford in one of the major Sachs monologues at the Seattle International Wagner Competition in 2006, where he swept all the major prizes. To my mind, he displayed the personality, the understanding, and the musicianship for the part—everything except the rolling, authoritative sound and sheer heft that would validate all the rest. Given his experience and the years that have passed, I had cause to hope he was ready now. But no, in the context of the complete opera, he made still less of an impression, lackluster at both extremes of his range, apologetic in his body language, like mine host of The Garter, vanishing into the woodwork.

And then there was the woodwork. Sir David McVicar's production—a shopworn four-year-old hand-me-down from Glyndebourne—transplants 16th-century Nuremberg to some Gothic Revival gazebo suspiciously reminiscent of Sussex on the cusp between Jane Austen and Charles Dickens. Think crumpled top hats and tea—tea!—from china demitasses.

I seem to remember good notices and crisp stage photographs from Glyndebourne the first time around, when the great Canadian baritone Gerald Finley was on hand for his first Sachs, and Sir David superintended the staging in person. Meticulous craftsman that he is, he would surely not have tolerated the lighting we saw in San Francisco, which steeped key moments of the action in deep gloom. Nor can I imagine that his choristers would have come across as so collectively lifeless, or that individual mastersingers would have gotten away with such shameless mugging. (Looking at you, Kunz Vogelgesang!) Quality control over the life of a production is a challenge in the best of times. What with revolving casts and serial transfers, it can seem truly impossible.

The performance I attended was the fifth of six. A matinee remains, on Sunday, December 6.