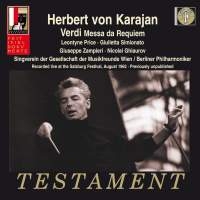

VERDI: Messa da Requiem

Leontyne Price, Giulietta Simionato; Giuseppe Zampieri, Nicolai Ghiaurov; Vienna Singverein, Berlin Philharmonic, Herbert von Karajan. Testament SBT 1491

*

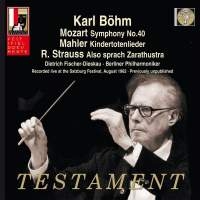

MOZART: Symphony No. 40; MAHLER: Kindertotenlieder; R. STRAUSS: Also Sprach Zarathusthra

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau; Berlin Philharmonic, Karl Böhm. Testament SBT 21489 (2)

To judge by two previously unpublished recordings lately sprung from the vault of Austrian Radio, a five-concert residency at the Salzburg Festival in 1962 found the Berlin Philharmonic in peak form. Courtesy of Testament, we may travel back to August 9, when Herbert von Karajan led off at the Grosses Festspielhaus, capacity 2,000-plus, with the Verdi Requiem, and also to the finale on August 19, when Karl Böhm presented, in the same hall, a mixed bill of Mozart (Symphony No. 40), Mahler (Kindertotenlieder) and Richard Strauss (Also Sprach Zarathustra). The other concerts, conducted by István Kertész, William Steinberg and Rudolf Kempe, took place in the art nouveau jewel-box at the Mozarteum, seating a select 800. Those were red-letter occasions, too. For Kertész, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, who walked on water, sang Richard Strauss's beloved Vier Letzte Lieder, a specialty of hers.

A theme common to the Karajan and Böhm programs would be death and transcendence, manifested by Verdi on the cosmic scale and by Mahler in the private meditations of a father mourning beloved children snatched away before their time. Under Böhm's baton, the instrumentalists rely chiefly on the eloquence of transparency and restraint. At the start of the final song, in which the scene-painting bristles with unruly, tempestuous energy, the playing is neither disheveled nor even loud. Elsewhere, the magical glockenspiel and celesta convey notes of consolation from the beyond.

In principle, Böhm's lyricism and the fanatically analytical manner of the soloist might seem bound to clash, yet they mesh beautifully. At the top of his game, the masterly Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau teases out fine points syllable by syllable, keeping song and speech in perfect balance. Here, within a single phrase, he both snarls and caresses. There, within a single note, he turns inward, drawing the curtain, as it were, or dimming the lights.

For some, the old complaint that Fischer-Dieskau smothers spontaneity in calculation will still apply, yet you could not call his performance cold. He never stood still as an interpreter; an edge of the unpredictable always remained. But indicating came more naturally to him than surrender to emotion — which may be one reason his gruff, metronomic, even catatonic manner when observing the children's bereft mother in the third song seems so direct and true to life.

For some, the old complaint that Fischer-Dieskau smothers spontaneity in calculation will still apply, yet you could not call his performance cold. He never stood still as an interpreter; an edge of the unpredictable always remained. But indicating came more naturally to him than surrender to emotion — which may be one reason his gruff, metronomic, even catatonic manner when observing the children's bereft mother in the third song seems so direct and true to life.

In the Requiem, Leontyne Price leaps from the speakers, eyes wide at the apocalypse, blazing through the concluding "Libera me" with feral, Dantean astonishment. Giulietta Simionato utters the prophecies of the "Liber scriptus" with an even, darkly gleaming severity befitting the sibyls of Michelangelo. In the penultimate "Lux aeterna," she touches a very different chord. The soprano prima donna is silent in this movement, gathering her forces against the final onslaught. Meanwhile, the three lower voices in the quartet take their leave for the sphere of Light Eternal. Translucent in timbre and texture, Simionato points the way.

And the men? In the wake of the cataclysmic opening of the "Dies irae," Nicolai Ghiaurov tiptoes shell-shocked through the echoing void ("Mors stupebit"), but by the time his next solo ("Confutatis maledictis") rolls around, his lean, cavernous bass is flowing with a confident grace. A deer in the headlights, Giuseppe Zampieri rushes, scoops, and swallows bits of the "Ingemisco" here and there, but ultimately his open tone, varied palette of colors and sincere operatic ardor carry the day. In the recording studio, Karajan would probably have required another take.

And the men? In the wake of the cataclysmic opening of the "Dies irae," Nicolai Ghiaurov tiptoes shell-shocked through the echoing void ("Mors stupebit"), but by the time his next solo ("Confutatis maledictis") rolls around, his lean, cavernous bass is flowing with a confident grace. A deer in the headlights, Giuseppe Zampieri rushes, scoops, and swallows bits of the "Ingemisco" here and there, but ultimately his open tone, varied palette of colors and sincere operatic ardor carry the day. In the recording studio, Karajan would probably have required another take.

Many scholars and collectors prize unretouched, live recordings for just the sense of immediacy that a fleeting, "human" beauty mark underscores. With Böhm and Karajan in charge, you won't detect a whole lot of that. Sorry, Mozart! Sorry, Richard Strauss! Sorry, Wiener Singverein! There's no space here to go into further detail. It goes without saying that these archival performances stand the test of time, and the vintage mono sound passes muster by and large. At the same time, one may wonder: what, more than a half century after the fact, do these CDs tell us that classic commercial recordings of these same artists in this repertoire have not documented before? The truth? Not much.