Roles of saints, demons, and craggy souls grappling with last things came naturally to Finnish basso Martti Talvela. His timbre seemed primeval, his aura of another world. Not so incidentally, he stood a towering six foot seven inches tall. He was dancing at his daughter's wedding a quarter century ago when death struck him down at age fifty-four, an end his beloved Dostoyevsky could not have staged more cruelly.

Roles of saints, demons, and craggy souls grappling with last things came naturally to Finnish basso Martti Talvela. His timbre seemed primeval, his aura of another world. Not so incidentally, he stood a towering six foot seven inches tall. He was dancing at his daughter's wedding a quarter century ago when death struck him down at age fifty-four, an end his beloved Dostoyevsky could not have staged more cruelly.

Osmin, the overseer of the harem in Mozart's Entführung aus dem Serail, may seem a poor fit for an artist of this description. At the Metropolitan Opera, his calling card was his unsurpassed Boris Godunov, accounting for thirty-nine of his 116 performances in a dozen roles. By contrast, he had only four Met outings as Osmin; in two of these, he dropped out after Act II, leaving the final aria of cascading Handelian schadenfreude to his cover, Ara Berberian. (These were the only two Met performances he failed to complete.) Yet of Talvela's assignments, Osmin was reportedly his favorite.

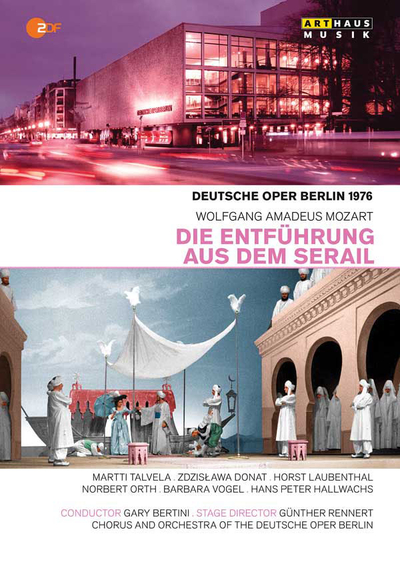

His enjoyment in an all-star Entführung from Bavarian State Opera in 1980, long available on DVD from Deutsche Grammophon, shines through, but theatrics get in his way. Done up first like Otello, then like Genghis Khan, then scrubbing in a bubble bath, Talvela comes off like the bumbling Giant in some panto Jack and the Beanstalk. What we see in a new Arthaus release, filmed at Deutsche Oper Berlin in 1976, looks simpler but strikes deeper. Here Talvela's Osmin neither calculates nor plays to the gallery. His loyalties, affections and sense of justice spring from an innocent heart. So, consequently, do his disappointments and feelings of betrayal. There's more of Papageno in this paper tiger than there is of Monostatos. And the sheer splendor of his voice, now velvety, now rugged as it charges and lilts through Osmin's tirades and ditties, can take one's breath away. What a fool the beauty is who rejects this beast.

On other counts, the performance is scarcely one for the ages. The orchestra conjures up bewitching colors, but on the podium Gary Bertini dawdles and rushes by turns; lapses in ensemble are not infrequent. A fashion-plate in her ostrich-feather hat, Zdzisława Donat's Konstanze dispatches her elaborate coloratura with wan grace. Horst Laubenthal has mellow notes for Belmonte's high-lying romantic phrases, but he loses allure most everywhere else. As an actor, he doesn't even try. (As was customary at the time, Belmonte's euphoric third aria, potentially his most ravishing moment, is cut. Probably no loss.) Barbara Vogel's Blonde revels in crystal timbre, elegant articulation and sparkling, quite individual rapport with both her suitors. As the enterprising Pedrillo, Norbert Orth handles the heroics and lyricism with lively assurance.

The production is by Günther Rennert, seldom mentioned nowadays, though he was a player back when top directors were content to serve a composer's vision without superimposing their own. The stage pictures are uncluttered, place and period are respected, and the story unfolds in orderly fashion. That's all good. Still, there's no turning back the clock. To our eyes, there is taste here, but little style. Put another way, nothing much bothers us, but nothing delights us, either.

That said, there are moments. Here and there Talvela's Osmin is shadowed by a mute, adoring sidekick (Wolfgang Leisky), the Moth to his Falstaff — a wonderful touch. And the festive finale acquires an unexpected tragic resonance. Until the last act, the attributes that define Hans Peter Hallwachs in the speaking role of the Turkish potentate Bassa Selim have been ramrod posture and a turban like a hot-air balloon. Silent as the music plays, finally free of that turban, bending to kiss Konstanze's hand in farewell, he emanates a stoic gallantry that speaks volumes of what might have been. One feels quite shaken.