Brooklyn, N.Y.

Brooklyn, N.Y.

A torrential raconteur, Aldo Mancusi traces what he calls his magnificent obsession to his father, Everisto, who in 1920 emigrated from Campania, Italy, to this, New York's most populous borough, while still in his teens. "He had about 70 Caruso records that he would crank up when I was 4, 3, 2, 1," Aldo said one recent morning. As curator and founder of the shrine grandiloquently styled the Enrico Caruso Museum of America, he was about to turn back the clock, flourishing a shellac disc dating to November 1902, the year the peerless Neapolitan tenor began recording.

"You have to change the needle every time or you ruin the surface," Mr. Mancusi noted, happily in possession of an inexhaustible supply. "This is why people were so strong back then," he added, powering up his Victrola the way you would a Model T. "I have a jukebox, too, but it's on tilt. 'Celeste Aida.'"

And through the glistening horn, moving air as if the singer were right there in the room, came The Voice: immediate, burly, vibrant, unmistakable. Yes, sound engineers through the decades have reissued these Golden Age mementoes time and time again, none more expertly than Ward Marston, whose boxed set of 12 CDs on the Naxos label encompasses the complete Caruso discography. But for the impact of the living presence, nothing touches the antique technology. There's a shaman's magic at work. To record, artists funneled their music into just such a horn, setting aquiver the needle that cut the groove. On playback, the process runs in reverse: A needle traces the groove, and the horn rings as it did the first time. Much is lost forever. But what remains is the real thing, unadulterated.

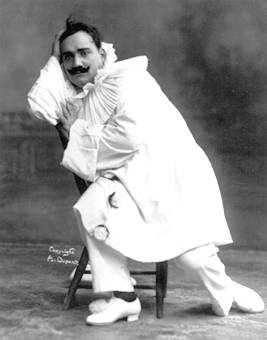

Mr. Mancusi, now 84, owns one original copy of each of Caruso's 250-odd recordings; polychrome porcelain collectibles in bell jars of Caruso in "Aida" and "Pagliacci," etc.; a costume or two he may or may not have worn; numerous tangy caricatures dashed off by the tenor's own inspired hand; plus various letters, ephemera and one of Caruso's only three authentic death masks. By Mr. Mancusi's own account, he has been amassing memorabilia for half a century, most of the pieces acquired, he says, at prices ranging from $500 to $1,000. Mr. Mancusi's devotion to his idol's memory has earned him the title Cavaliere Ufficiale of the Italian Republic, and he bears it proudly. The crowning honor is shortly to come: the rank of Commendatore, not the very highest Italy has to bestow, but Caruso himself received none higher.

In the old days, Mr. Mancusi kept his treasures at home at 1942 E. 19th St., on the first floor of one of the two-family houses typical of the neighborhood, Sheepshead Bay. Eventually the parade of friends and sometimes starry friends of friends dropping by on weekends got on his wife's nerves. "I don't even know these people," Lisa Mancusi is said to have protested, "but I have to serve them coffee and cake." So Mr. Mancusi moved the museum to the unit upstairs. There it has remained, open to the public on Sundays, by appointment, since 1990.

For a living, Mr. Mancusi "designed space," as he puts it. "Not outer space but inner space. I specialized in saving space, in doctors' and lawyers' offices. I had my own factory. I did well." His two miniature galleries—jammed but not cluttered—reflect his expertise. One is set up as a theater with two short rows of velvet seats. Not a square inch is wasted.

Caruso spent his last weeks at the Hotel Vittoria in Sorrento, Italy, overlooking the Bay of Naples, counting on the sun and sea of home to restore his shattered health. You won't miss what most aficionados believe to be the last photograph shot of him in his lifetime, looking out from a balcony, remote in wingtips, coat and tie. But behind the door at the top of the stairs, Mr. Mancusi keeps sequestered what seems a later picture, as macabre as Dorian Gray's. Posed by the same balustrade, swathed in terrycloth like a Roman senator at the baths, his eyes burning into the lens, an ashen Caruso displays the gash on his back from recent surgery for an excruciating lung infection. The expression is that of a stricken beast.

This harrowing, uncirculated image came to Mr. Mancusi from the nephew of one Dr. Antonio Stella, who treated Caruso in America before Caruso's ill-advised final voyage home. The photograph was enclosed with a letter to the physician, preserved in the same frame, in which Caruso describes, gracefully and without complaint, new complications and his self-directed attempts to cure them. In essence, he was combating an anaerobic infection with a first-aid kit. But then, this was in 1921, seven years before the discovery of penicillin. The missive had not yet reached its destination when Caruso lost the battle, at only 48 years of age. Mr. Mancusi, who frowns on the taking of photographs within his walls, is especially protective here.

What, a visitor gently wonders, will be the fate of his collection in times to come? "The Met would take it," he answers, transparently referring to the Metropolitan Opera, where between 1903 and 1920 Caruso, a company fixture, gave a staggering 863 performances. "But I would have to give them total discretion, and that won't happen. They'd cherry-pick what they think is the good stuff, and dump or sell the rest. I want the collection to go somewhere they'll promise to keep it together. Preferably in Manhattan."

Tragically, perhaps, the prospects for that seem infinitesimal. Robert Tuggle, director of the Met archives, tells me he knows of no overtures to the Met from Mr. Mancusi. "The scenario he has in mind belongs to the age of Belle Linsky or Robert Lehman," Mr. Tuggle says, citing patrons who donated their collections to the Metropolitan Museum of Art on condition that they remain intact. "No museum collects that way anymore, nor should they. Of course curators must be rigorously selective. Most museums and libraries will no longer accept 78 records unless they can choose a handful to fill in gaps."

Sic transit gloria mundi? Or could a White Knight still ride in to save the day?

"I've had offers," Mr. Mancusi says, "but nothing in Manhattan."

An angel passes as his gaze travels around the room.

"People do different things with their money," he says. "One of my brothers used to buy boats. First, it was a boat for four people, then for eight people, then one that sleeps six. That kind of thing never ends. I bought stuff for the museum. I love every nook and cranny."