The Queen Strikes Back! So much for her plunge into Eternal Night at the close of Die Zauberflöte. Tamino and Pamina have yet to rise from their wedding feast when Her Troublemaking Highness is discovered plotting outside. Venus and Adonis, no less (Ladies 1 and 2 in disguise) mobilize to wreck the newlyweds' happiness. Then presto! Unbidden allies appear — the paper tiger Tipheus, king of Paphos, his aim to overthrow Sarastro and win Pamina's hand, mainly by means of idle threats from his sidekick Sithos. In the temple precinct, a reluctant Sarastro clings to power, hustling Pamina and Tamino into a maze for redundant trials just when they ought to be taking charge. Meanwhile, Monostatos is stalking Papagena.

The Queen Strikes Back! So much for her plunge into Eternal Night at the close of Die Zauberflöte. Tamino and Pamina have yet to rise from their wedding feast when Her Troublemaking Highness is discovered plotting outside. Venus and Adonis, no less (Ladies 1 and 2 in disguise) mobilize to wreck the newlyweds' happiness. Then presto! Unbidden allies appear — the paper tiger Tipheus, king of Paphos, his aim to overthrow Sarastro and win Pamina's hand, mainly by means of idle threats from his sidekick Sithos. In the temple precinct, a reluctant Sarastro clings to power, hustling Pamina and Tamino into a maze for redundant trials just when they ought to be taking charge. Meanwhile, Monostatos is stalking Papagena.

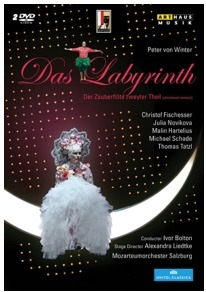

Question, if you will, the need for a second Zauberflöte seven years after Mozart's death. But Emanuel Schikaneder, impresario of the Theater auf der Wieden, prolific librettist and frequent star of his own stage, knew what he was about. Das Labyrinth oder Der Kampf mit den Elementen ("The Labyrinth, or The Fight with the Elements," 1798) was conceived and expressly billed as Part 2 of the earlier opera. As before, Schikaneder contributed the book and lyrics. Though many from the original cast had moved on, he once again claimed Papageno's scene-stealing feathers. (Mozart's sister-in-law Josepha Hofer made a comeback as the Queen of the Night.) Peter von Winter, in his day a name to conjure with, wrote the music. Do his originality and invention measure up to Mozart's? Guess. Yet Das Labyrinth held the stages of European music capitals for three decades.

As documented at the 2012 Salzburg Festival, on the opening night of the modern premiere, the music shows considerable verve. Apart from triple fanfares, five-note Pan pipes and a duet for Pamina and Papageno that hints at possibilities beyond their old friendship, references to Mozart are more oblique than overt. Recitative, more prevalent here than in Mozart's opera, is wooden.

Paced with a passion by Ivor Bolton, tirades for the Queen and the war cries of the priests (pacifists no longer) charge forward on vigorous bass lines that hark back to Handel even as they point ahead to Beethoven. Glamorous in a ballgown seemingly fashioned from scorched meringue, Julia Novikova's Queen struggles with her coloratura and top notes. Sarastro's hymnic mode has taken on a gentler bloom, which is no problem for the thoughtful Christof Fischesser's lean, incisive bass.

Dramatically, Pamina has dwindled to a cipher, yet flourishes here and there demand the flash of the seraglio-bound Konstanze; Malin Hartelius carves the arabesques elegantly, though with a steely edge. Tamino takes a step or two in the direction of Rossini, to the evident delight of Michael Schade. A multigenerational brood of Papagenos pipe up in a catchy populist vein that lacks the Ur-Papageno's pristine naïveté, though as the cock of the walk, the sweet-voiced, fresh-faced Thomas Tatzl goes far to restore it. But the knockouts are two men in armor with a difference. The fine low voices and energized articulation of Clemens Unterreiner's dark Tipheus and Philippe Sly's blond, leonine Sithos pack quite a charge, especially when they are singing in tandem. (Sly's darkly gleaming low register and romantic, easy top are a particular joy.)

Schikaneder envisioned nonstop mechanical stage marvels. Mounted in a baroque courtyard, Alexandra Liedtke's production makes do with a touch of toy theater here, a hint of Vegas glitz there, and in a pinch a bunch of balloons. The eye-popping costumes — illuminated lampshades for the Three Spirits, lederhosen for Tamino, don't ask about the doily halos — load up Austrian folk finery with crazy Big Top pizzazz.