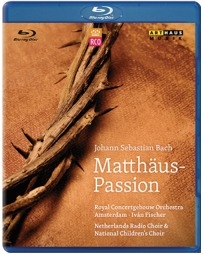

As the world knows, Bach conceived the St. Matthew Passion as a marathon church service. Now that theater artists of many persuasions have staked claims on the score, can the oratorio treatment generations of music-lovers grew up with still compete? This no-frills performance by the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra Amsterdam, filmed in 2012, proves that it can.

No, there is nothing here to set beside (say) the soloists' histrionic ecstasies of personal identification in the recent Peter Sellars "ritualization" of St. Matthew for the Berlin Philharmonic. But the Concertgebouw team, led by Iván Fischer, needs fear comparison with no one, and the involvement and concentration the camera discovers on the musicians' faces tell an eloquent story.

You'll see no playacting here. You'll hear no reaching for pitches, no smudging of the little notes. The performers — instrumentalists and vocalists alike — merely execute their assignments as immaculately and expressively as they know how. The storytelling from the gospel proceeds at an unhurried pace, yet the tempos in the formal musical numbers tend to the swift, underscoring the inexorable flow of foreordained catastrophe. Bach's audiences would have sung along with the scattered Lutheran chorales. The Amsterdam audience does not, but the unadorned interludes register as special moments for private reflection.

What, though, of spectacle? Of pageantry? There's none of that. The men's dress code calls for business suits and straight neckties. For the women, it's basic black, enhanced here by a burgundy shawl, there by sequins that mimic lace by Rembrandt. The boys and girls of the National Children's choir wear dark slacks and white oxford shirts, shirttails out, collars unbuttoned.

There is one apparent stroke of the theatrical, but its purpose turns out to be purely musical. It occurs in the opening chorale, to which the children's choir contributes a hymn to the Lamb of God. Too often, their line is lost in the entirely different words and music of the orchestra and adult chorus's churning lamentoso. Here, the children are clustered around the maestro, who draws forth their pealing voices so that we truly hear them. In keeping with Bach's use of a double orchestra and a double chorus on facing galleries of the Thomanerkirche, Fischer positions individual mixed complements of instrumentalists and singers at far sides of the stage of the Concertgebouw. He even fields two quartets of vocal soloists, from many nations. The eight artists' voices are lean, even, and transparent yet distinctive. All articulate with the clarity of virtuoso instrumentalists. All own the text. Each deserves individual appreciation that space here will not allow.

Three of them, however, tie, as it were, for first place among equals. Mark Padmore, tenor, and Peter Harvey, bass, double as the Evangelist and Christus, respectively. Padmore's Evangelist recites gospel with unsurpassed sensitivity, maintaining his unpinched, sunny timbre even in the incessant top notes of his wickedly high-lying recitatives. Harvey's Christus seeks majesty in plain-spoken gentleness and never fails to find it. The men's arias and arioso bring into play their poetic phrasing and the full sheen of their voices. Prize arias for alto — in particular the celestial "Erbarme dich" — fall to Ingeborg Danz, whose delivery is as piercing as it is aristocratic.