Born in Honolulu to a Polynesian father and an American mother, little Mahani was soon whisked away to the rock in the South Pacific that descendants of the original settlers—her father's people—know as Rapa Nui. It really is a rock. Located 2,200 miles due west of the Chilean coast, with a landmass of just 63 square miles and a population of around 7,700, Rapa Nui is the home of the 1,000-plus moai, monolithic stone deities arranged in rows on the shores, with their backs to the ocean. English speakers know the place as Easter Island.

The story of little Mahani's discovery of an upright piano in the home of an itinerant violinist briefly settled on Rapa Nui, of her studies on the Chilean mainland, at the Cleveland Institute of Music, and the Hochschule für Musik Hanns Eisler, Berlin, and her emergence as a concert artist ready for the international stage borders on fantasy.

So does the sequel in which, on the cusp of a glittering career, Teave pivots and goes back home to give back. Founded in 2012, the Rapa Nui School of Music and the Arts [https://tokirapanui.org/en/ngo-toki.html] teaches indigenous traditions as well as the "classical," Eurocentric curriculum. A news cycle or two ago, this hardy little institution—housed in a handsome, energy-efficient structure built of recycled tires, cans, and bottles—got considerable exposure. With the surprise release of Teave's two-CD debut album "Rapa Nui Odyssey," which topped the Billboard Traditional Classical chart, Teave's name and likeness were suddenly flashing across the web, starting with Graydon Carter's electronic newsletter Air Mail, the major news channels, and the pages of the New York Times. Now there's a documentary about her, narrated by Audra McDonald, plus a charming children's book].

This fall, Teave, now 40, emerged from isolation for a twelve-city North American debut recital tour, which also included a date or two with orchestra. Major stops included the brand-new Perelman Performing Arts Center in Lower Manhattan, Toronto, Cleveland, the Kennedy Center, and Seattle, with frequent classroom visits along the way. On the final leg, Teave returned to the Aloha State for the first time, playing on three islands.

On November 10 , Teave's penultimate date brought her to the 1,200-seat Castle Theater at the Maui Arts and Cultural Center, inaugurated in 1994, and by a considerable margin the best-appointed concert hall in the island chain. Two nights later came the finale in Honolulu.

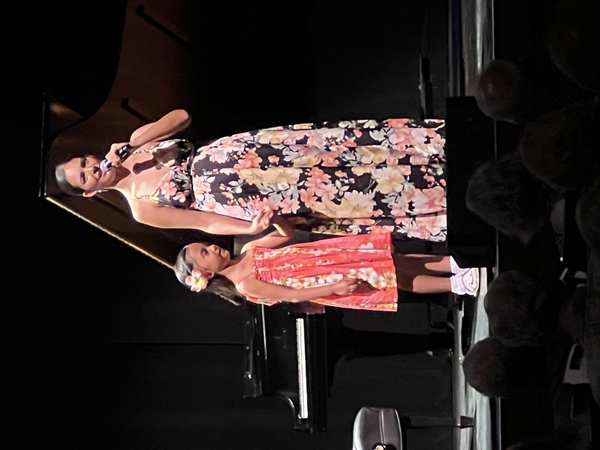

A star or two in the family. Mahani Teave and her daughter Tahai Teave Icka onstage at the Maui Arts and Cultural Center. |

"The reason I have a student traveling with me," Teave explained with what would prove over the evening to be her characteristic smiling modesty and grace, "is that she's my daughter." Seven-year-old Tahai then entered, piping the chant "I hē a Hotumatu'a" with unadorned eloquence.

That selection appears as the final track of Teave's album, and it's a beauty, grave yet serene, with phrases that always linger a few repeated notes longer than the (Western?) ear expects. The arrangement is by José Miguel Tobar, a teacher in the school on Rapa Nui, who has an unabashed flair for lavish coloristic effects. Yet under Teave's hands, none of the pianistic fancywork feels showy for the sake of show. Instead, the music seems to scatter and hover all at once, like spindrift over breakers or sunlight caught in veils of mist. Two selections from Alejandro Arevalo's Suite Rapa Nui followed ("E te 'ua Matavai," "Mai Hiva te 'Ariki"). These are, if anything, more elaborate, shot through with glissandi up and down the length of the keyboard. Again, Teave delved beyond the notes to release their contemplative and poetic potential.

The balance of the first half was devoted to Chopin in many moods, mixing and matching nocturnes (op. 9, no. 1, and op. 72), mazurkas (op. 67, nos. 2 and 4), the Barcarolle op. 60 in F# major, and finally the Scherzo no. 1 in B minor, op. 20. The second half matched J.S. Bach's Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue in D minor BWV 903, proceeded with the high romantic chromaticism of Franz Liszt's Ballade No. 2 in B minor and Sergei Rachmaninoff's Moments Musicaux op. 16, nos. 1 and 4. The pattern set in the Polynesian arrangements held true here, too. Teave doesn't showboat, intellectualize, or "make a statement." She calls no attention to her technique. She puts herself at the service of the music and lets it bloom.

That's not to say that her playing lacks personality. In the Bach, Teave distinguished feelingly between the demonic yet often lightly textured swirl of the fantasy and the rigorous yet never ponderous architecture of the fugue. She was no less commanding in the Liszt ballade. According to her fellow Chilean Claudio Aarau, who studied with a protégé of the composer's, the musical narrative recapitulates the Greek romance of Hero and her lover Leander, who would swim to her by night across the treacherous Hellespont, where at last he drowned. Whether that's true or not, Teave orchestrated the surging elements (interior and external) of the musical narrative with vivid imagination. In the Chopin barcarolle, she set the mind adrift on still waters that ran deep. In the Chopin scherzo, she handled the brusque stops and starts with moody, mercurial wit.

As an encore, Teave offered Schubert's Impromptu in E-flat major, D. 899 No. 2, rippling through the moto perpetuo flurries of the opening pages in silken form, then rolling out the middle section in a plush, spacious legato of sublimity that was understated, yet impossible to miss.