Conrad L. Osborne: "I don't want to write generalizations. I want to show what goes on inside: the things that make an opera performance credible, that make it powerful—or not." |

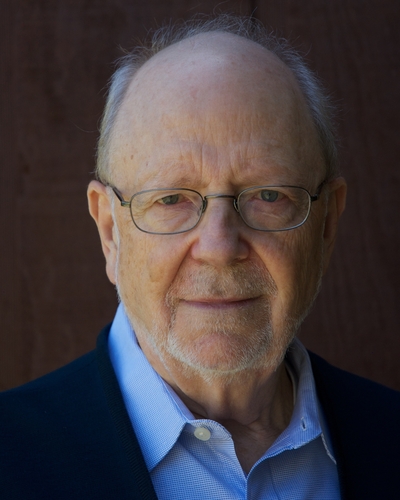

To his judgments Osborne brings not only his acuity of eye, ear, heart, and mind, but professional experience as a classical singer, stage actor, senior arts administrator, and consultant—all this, plus a prodigious work ethic. At 84, he maintains a busy voice studio. The voluminous manuscript of Opera as Opera (786 pages, plus acknowledgments and index) took shape alongside his other obligations over the course of 18 years.

"It took persistence," Osborne said recently. "On an extended project, you just have to get up every day, do some, a little or a lot, good or bad."

Though one might guess otherwise, he hails from the heartlands. "I was born in Lincoln, Nebraska, in the midst of the Great Depression. My dad was a schoolteacher, and also a singer who taught English and speech in college. For several years, we had to move a lot, from small town to small town, until he got work in the school system in Denver. We settled in the New York area in 1943, when I was nine."

Musically, the postwar period in New York is remembered as a Golden Age, with the Metropolitan Opera in its glory, the populist New York City Opera rising fast, not to mention a burgeoning concert scene.

Osborne's first brush with opera came in dress rehearsals involving his father. The older Osborne also sang in the chorus in Arturo Toscanini's broadcasts of the Berlioz treatments of Romeo and Juliet and Faust, which his lucky son caught live at the NBC Symphony Orchestra's legendary Studio 8H. "I got hooked on my dad's record collection from the age of five," Osborne notes. "That, and hearing him sing around the house."

One immortal he might well have heard in person but missed was Kirsten Flagstad. "I was in prep school," he says, "and the dates never worked out. I intended to go to her farewell performance with the Symphony of the Air at Carnegie Hall. And I was prepared to walk home after. But standing room turned out to cost the unheard-of sum of three dollars—at the Met you paid $1.25—and all I had was $2.97. I was three pennies short.

"Yes, that was very poignant. But I heard Tristan und Isolde and Götterdämmerung with Lauritz Melchior and Helen Traubel and Ferdinand Frantz and Dezső Ernster and Herbert Janssen. Though I was very young, people like that put an idea in my ear about how Wagner should sound. The Herbert Graf production of Don Giovanni, with Eleanor Steber, Lisa Della Casa, Cesare Siepi, and Fernando Corena, designed by Eugene Berman, was my first experience with what is now an extremely conventional, unifiedproduction at a very high level. My first Otello was a matinee with Renata Tebaldi, Mario del Monaco, and Leonard Warren. Thatwas indelible. Great singers knock your socks off." One more in that league was Jon Vickers as Peter Grimes, in the Met's opening season at the new house at Lincoln Center.

Vocal impact is part of Osborne's story, but it's not all of his story. Speculative pages of Opera as Opera put forward Osborne's explanation for what he sees as the creative drought that has blighted opera for the past hundred years. In a nutshell, he argues that composers and librettists of the grand epoch from the mature Mozart to Puccini kept recycling a single tale rooted in the chivalric schema of courtly love. With the general cultural wreckage of the Great War, that "redundant metanarrative" was swept away, and the people who wrote operas never found another to take its place.

From limited evidence, Osborne draws sweeping conclusions. Tchaikovsky's Mazeppa, Prokofiev's Betrothal in a Monastery, Halévy's La Juive, Herbert Wernicke'sFrau ohne Schatten for the Met, an apparently revelatory Traviataat New York City Opera that never made it onto the international radar (Frank Corsaro directed; Patricia Brooks starred): from microscopic analysis of pregnant details from productions like these, Osborne builds his case for operatic practice in which word and music are one, the ear takes precedence over the eye, the stage is not just a space but a place, and the intrinsic, purposely elevated rhetoric of the medium is embraced rather than undercut by dictatorial directors and quisling conductors preoccupied with abstract musical perfection.

"When I was young," Osborne notes, "I acted a lot. So, I've always had a feel for looking at opera from a theatrical point of view. That's a big part of what opera means to me. I suppose it will drive some readers to madness, the way I go into very great detail about just a few pieces, working from very specific points of view. But that's what's necessary. I don't want to write generalizations. I want to show what goes on inside: the things that make a performance credible, that make it powerful—or not."

What's Osborne's answer to those who may call him conservative, even reactionary?

"Those are political terms. I have a hard time accepting them with respect to art. It's a matter of ethics. Either you have a set of principles you work by or you don't. But there are certain things about singing that are absolutes. Either you consummate the demands of the music or you don't."

[1]An invaluable though incomplete archive of back issues of High Fidelity in PDF format may be found at https://www.americanradiohistory.com/High-Fidelity-Magazine.htm. Among the major Osborneiana readily accessible there are surveys of the operatic Verdi (October 1963), Mozart (November 1965), and Wagner (first installment, November 1966), plus his dazzle-dazzle "Diary of a CavPag Madman" (November 1979), an early harbinger of Opera as Opera.