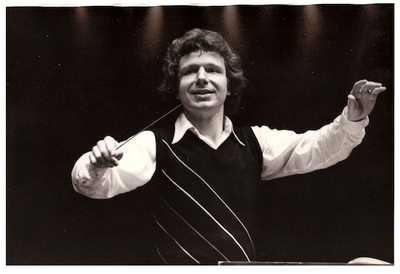

Trial by fire. John Mauceri in rehearsal for his professional debut, with the Los Angeles Symphony, 1974. |

John Mauceri's book Maestros and Their Music: The Art and Alchemy of Conducting takes me back a quarter century to 1993-94, when I organized a season of live interviews with leading conductors at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Together with Hilde Limondjian, the Met's indomitable impresario of Concerts and Lectures, I came up with seven names. One played hardball over the penny-ante issue of rights to a transcript but then relented. One temporized past the point of absurdity, probing through an intermediary who else had committed. In the end, he came through, too. The other five signed on instantly, no strings. Boasting a guest list of Daniel Barenboim, Pierre Boulez, Valery Gergiev, James Levine, Kurt Masur, Riccardo Muti, and Sir Georg Solti, "Conductors in Conversation" sold out by subscription and later aired for home listeners on WNYC.

We covered a lot of terrain. For me, perhaps the single most revealing moment came in dialogue with Kurt Masur, who said that some extremely despondent piece of music ended on a note of hope. I remarked that I had heard him claim the same thing for a number of other bleak compositions and asked if he might be afraid to send the audience home in a state of hopelessness. A long pause followed. "Yes," he said at last. "I think I am."

As for the bedrock questions—What is the role of the conductor? What does the conductor do?—the answers I came up with for myself were these. The role is twofold: in rehearsal, to act as surrogate for the composer, and in concert, as surrogate for the audience. Either way, a great conductor will be one who wants more. More of what? More sensitivity, more expression, more accuracy, more fire, more individuality, more discipline, more audacity, ...—take your pick.

For those who happened to miss that season at the Met, Maestros and their Music: The Art and Alchemy of Conducting offers a top-notch alternative. Apparently, the world has been waiting: to date, translations into Italian, Russian, and Japanese are in the works, plus not one but two versions in Chinese.

Hugely versatile, technically bullet-proof, artistically driven, Mauceri belongs to the class of practitioners of his art whose merits have kept him in constant worldwide demand for a half century without quite winning him a pedestal among the legends such as my seven All Stars or the three he names as mentors: Leopold Stokowski, Carlo Maria Giulini, and Leonard Bernstein.

Perhaps for that reason, his history and analysis of his profession are as enlightening as they are down-to-earth. He has seen it all, knows where the bodies are buried, and makes no bones about naming names.

The panorama of his profession is organized in masterful fashion, and the prose sparkles. Opening with a short history of conducting, he explains not only what came to pass but also why it did, as well as the ways an increasing reliance on conductors shaped new ideas of what kind of music could even be written and performed. Chapters on technique, on learning a score, and on the training of a conductor follow.

Examining scores under the microscope, as the responsible maestro must, Mauceri sheds light on key moments of Aida, La Bohème, and Porgy and Bess. Other lessons are delivered via anecdote. Taking Mahler's counterintuitive but meaningful and meticulous tempo markings at the start of the Fourth Symphony to heart, Mauceri once received a slap on the wrist from a British critic, who noticed what was happening but had no clue why.

"Was I right?," Mauceri asks not quite rhetorically. "Yes. Did I convince? No." Checking a landmark New York Philharmonic recording led by Bernstein, Mahler champion supreme, Mauceri wondered why Bernstein had overlooked the instructions in question. "I chickened out," Bernstein confessed. (Speaking of Bernstein, you'll want to hear about his lunch in Salzburg, at home with Herbert von Karajan.)

Owning up to incidental frustrations, Mauceri steers clear of self-pity. He is open in sharing his disappointment at return engagements that failed to materialize. To this day, when critics make complaints based on prejudice or preference rather than research into the score, he finds it "quite simply, annoying."

Elsewhere, Mauceri examines how and why no two conductors' performances are alike, how and why recordings and live performance differ in their very nature (notably in their intervals of silence). He has trenchant observations on a conductor's relationship with the music, the musicians, the audience, the critics, and owners and management. His experience as a road warrior—weighed down with orchestral scores, coming back to his hotel for a post-concert sandwich assembled from the buffet at breakfast—crushes any notion of the glamour of the job. The alchemy hinted at in the book's subtitle comes into its own in the final pages ("The Mystery: Everything and Its Opposite"). On mystique, that indispensable yet most gaseous quantity in the equation, Mauceri is more matter-of-fact than most.

But the most telling part of the book may be the chapter "Who's in Charge?" Here, Mauceri anatomizes the politics of the concert hall and the opera house with clinical, devastating precision. Suffice it to say that power may not lie where a civilian might expect. There's Francesca Zambello in Washington, either clueless or indifferent about Gershwin's markings in Porgy and Bess, insisting on adjustments. And then there's Beverly Sills, a diva in twilight, rehearsing La Loca, written for her by Gian Carlo Menotti. The title character Juana, mother of the future Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, would be both her last role and the first written to order for her. After the world premiere in San Diego, the fledgling Mauceri was brought in ("I do not remember why") to conduct the revised version at New York City Opera.

"Gian Carlo, I told you no changes," Sills reprimanded Menotti at the first New York rehearsal when he pointed out that a bit of blocking made no sense. Moments later, Menotti had decamped with what appears to have been remarkable composure. "Who does he think he is?," Sills fumed. "Does he think these performances are sold out because of him?"

Newly established in New York with a wife and one-year-old to support, with no immediate prospect of other work, Mauceri kept his head down. The better part of a lifetime later, he wonders if he should not instead have left in solidarity with the composer. But perhaps it was not just the paycheck that kept Mauceri on the piano bench. As he writes in another context, "music owns us, in the same sense that the land owns the farmer."