God in the spin cycle, courtesy of William Blake (ca. 1805). |

In 1973, when I was cramming for orals in pursuit of a Ph.D. in comparative literature, my principal cheat sheet was the spanking-new Oxford Anthology of English Literature, the new kid on the block formerly monopolized by Norton, and supposedly more in touch with current scholarly tastes and trends. And there, in the first edition, I read this in a note on William Hazlitt: "Of the very large canon of his work a chief part was written for periodical publication, usually in haste under the pressure of deadliness."

By this time, I had cranked out a few periodical publications of my own and could tell just what the author had in mind. I so hope the reading has survived untweaked in subsequent print runs. I treasure that extra s no less than the apparel of Adam and Eve in an early English Bible published in Geneva in the late 16th century, according to which the sinning couple, discovering their nakedness, "sewed fig tree leaves together, and made themselves breeches" (Genesis 3:7). Later texts substitute aprons, coverings, loincloths, clothes, or girdles; some avoid the noun altogether ("they sewed fig leaves together to cover themselves"). Scholars and collectors value "Breeches Bibles" highly; for copies currently on the market, I've seen prices ranging from slightly over one thousand to slightly below one hundred thousand. But compared to the rare "errors, freaks, and oddities" or EFO's most coveted by philatelists, these are bargains. At auction, the postage stamp known as the "Inverted Jenny," issued by the United States Post Office on May 10, 1918, has fetched well over a millions dollars.

Precious, imperfect: the Inverted Jenny, worth a cool million, give or take. |

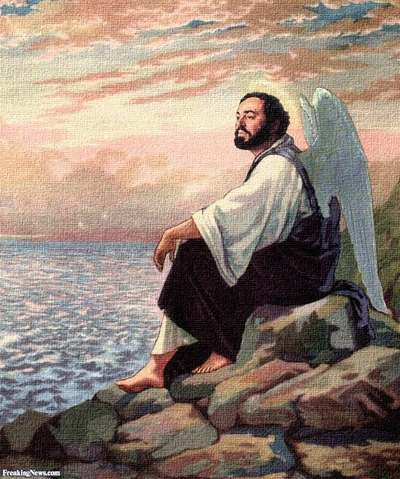

Life, we are often told, is not a dress rehearsal. And neither are dress rehearsals opening nights. Early one afternoon in 1993, the sight of the portly Luciano Pavarotti in downy angel's wings brought a smile to invited guests at the generale of the Metropolitan Opera's premiere production of the young Verdi's I Lombardi alla prima crocciata (The Lombards in the First Crusade). I, for one, was enchanted. After all, Pavarotti's character had died a saintly death in the scene before, was now returning to his beloved in a dream with gladsome tidings from beyond. But the stage director's gentle naïveté cut no ice with the general director, who consigned the feathers to mothballs, for good. The paying audience had no clue what they were missing.

I'm not making this up, you know. Luciano Pavarotti more or less as he appeared in the dress rehearsal of Verdi's I Lombardi at the Metropolitan Opera (FreakingNews.com). |

Any literate proofreader—any child in times not so long past—could have corrected the obvious scribal error, but where are such folk today? For now, the electronic dictionaries we trust in too much balk at bad spelling and verbs and subjects that don't agree but little else. One of the smarter programs might propose to morph the common noun into a brand name by uppercasing the w: a fix to gladden the heart of Hazlitt himself, cleanliness being next to godliness and all. But would such programs come up with the substitute our author really needs? As Eliza Doolittle would say, "Not bloody likely." If they only had a brain.

Yet this little cliffhanger had a happy ending. Before the first edition went to press, some sharp-eyed human with a blue pencil (the author? a hired hand? who cares...) chucked old I Am that I Am out of the whirlpool into the whirlwind, where He belongs.