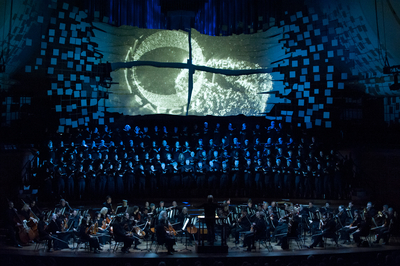

The Missa Solemnis spectacular conceived and conducted by Michael Tilson Thomas: religious pageantry for the concert hall/Photo by Stefan Cohen |

You will have guessed that I could have done without all the added value. But there is no denying its appeal to otherwise indifferent segments of the contemporary audience. Consider the so-called "ritualizations" of Bach's St. Matthew and St. John Passions mounted by Peter Sellars for the Berlin Philharmonic under Simon Rattle. Personally I have less than no use for the playacting, yet general audiences turn out in droves, dissolving in tears side by side with jaded cognoscenti. Let's not forget, however, that the Passions have a story line, by some lights the greatest ever told. Not so Beethoven's hieratic progression of supplication, praise, and doctrine, to which the singers enacted earnest charades of existential yearning and bewilderment. Who will fault such responses? And listeners may like to identify with them. Yet isn't the enterprise inherently redundant, erasing the message to glorify the messenger? If it takes showmanship to sell you Beethoven, is it Beethoven you're really buying?

Small wonder in such circumstances that those charged or self-appointed to report (critics!) will focus on the aspect of the performance that in truth is most extraneous, the same as I have done here. A listener in blindfold would more likely speak of a lucid, sometimes transcendent account of the score, led with a seasoned mastery extending from the grand design to the minute particulars. Articulate, expressive, and deeply engaged, the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra and Chorus rose with confidence to Beethoven's every challenge.

Contrary to usual concert practice but in keeping with the representational affectations of the affair, the vocal soloists were required to sing from memory—a very tall order indeed in repertoire of this description. Brandon Jovanovich, best known for full-blooded operatic assignments, brought to the tenor's gentlest episodes an otherworldly, honeyed radiance many a colleague in the lyric Fach might envy. No less remarkable, Joélle Harvey aced the soprano's daredevil flights with shimmering clarity and ease. Sasha Cooke lent the introspective mezzo part deeply intimate, personal inflections. As nominal anchor of the quartet, the bass Shenyang got rather lost in the shuffle, sounding grainy and out of focus. For the violin solo of the "Benedictus," which steals into consciousness like the Pentecostal flame spiraling down from on high, the concertmaster Alexander Barantschick stepped away from his chair and sheet music by the podium to join the singers on an upper platform to pour out his heart and soul as they looked on.

As so often, that solo was the crowning glory of the evening. And come to think of it, so it was in this same hall exactly four years ago, when the same conductor led this same violinist, orchestra, and chorus (but a different quartet of soloists) in a concert Missa Solemnis without bells and whistles, and not a whit the poorer for their absence. The opposite, I should say.